Few apps available for the iPad sell for $300—and even fewer are considered a bargain at the price. But "Speak for Yourself" turned consumer-grade tablets into sophisticated Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) devices for those struggling to speak due to issues like autism; standalone hardware offering the same capabilities goes for up to $15,000.

The software changed lives. Dana Nieder's daughter Maya was unable to speak on her own, and the recent Speak for Yourself app proved intuitive enough that the four-year old could use it almost immediately. The results amazed Nieder, who wrote about them on her blog:

Maya can speak to us, clearly, for the first time in her life. We are hanging on her every word. We’ve learned that she loves talking about the days of the week, is weirdly interested in the weather, and likes to pretend that her toy princesses are driving the bus to school (sometimes) and to work (other times). This app has not only allowed her to communicate her needs, but her thoughts as well. It’s given us the gift of getting to know our child on a totally different level.

Then, on June 4, Apple pulled Speak for Yourself from its App Store after two companies complained about patent infringement and filed a separate lawsuit against the app's developers. Speak for Yourself rushed to court to complain that its business had been "sacrificed to Plaintiff's commercial greed" without any sort of judicial ruling, but the court declined to take any immediate action. The Speak for Yourself app was gone and its developers had no other lawful way to sell it. They were worried—and angry.

So was Nieder. Sure, she had two copies of the program on the family's twin iPads already, but what would happen when Apple pushed out some new iOS update that broke compatibility with Speak for Yourself? What would happen when Maya dropped an iPad?

Worse yet, Nieder wondered, "What would happen if [Plaintiffs] contacted Apple and asked them to remotely delete the copies of Speak for Yourself that were already purchased, citing that the app was (allegedly) illegally infringing upon their patents, and stating that they wanted it entirely removed from existence?"

"Some similar features"

Speak for Yourself does not appear to be a highly capitalized organization. The founders' photo is out of focus; the site itself was built with GoDaddy's "WebSite Tonight" service.

The company is run by Heidi LoStracco and Renee Collender, both speech pathologists who "work exclusively with clients who are functionally nonverbal." Working with nonverbal autistic children, the pair found that a decent percentage could become verbal after using AAC tools for some time. When the iPad came out and school districts and clinics flocked to it as a way to deploy AAC apps for kids, LoStracco and Collender were often consulted to tweak the software packages—and the results never satisfied them. When they began getting inquiries about this "every day," the pair decided to author their own iPad AAC app. Speak for Yourself was born in 2011.

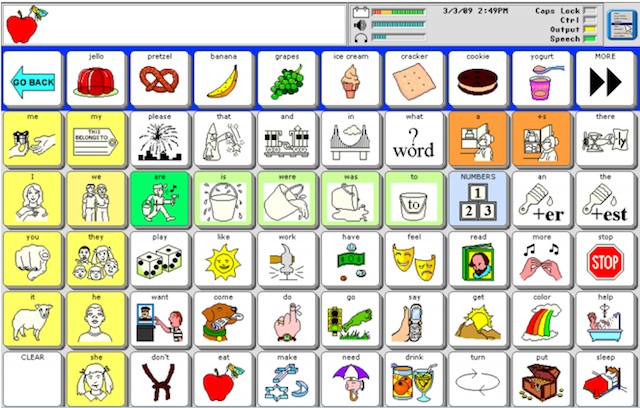

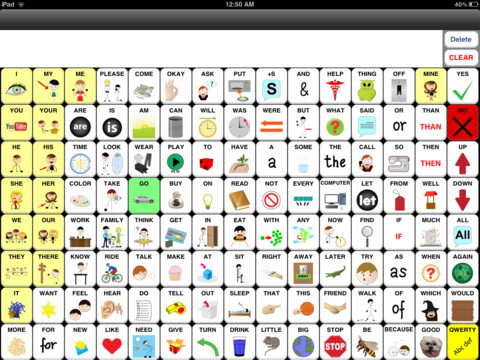

The app's homescreen offers 119 "core" words, like "with," "said," "go," "I," "want," "yes," and "no." Touching a word brings up other sets of words; touch "eat," for instance, and the next word screen brings up only food items. Users familiar with the system can quickly select words and string them together into sentences; a text-to-speech synthesizer can then read them out for others to hear.

This was far cheaper than dedicated AAC devices, such as those produced by the Prentke Romich Company (PRC) of Ohio. But Speak for Yourself offered a lot of similar functionality; as one December 2011 review noted, "Speak for Yourself's home screen looks a bit like a PRC device and overall has some similar features."

PRC came to the same conclusion. On February 28, 2012, the company joined forces with Semantic Compaction Systems, from which it licenses some of its key technology, and filed a federal patent infringement lawsuit in Pennsylvania against Speak for Yourself.

The two Speak for Yourself founders had infringed on "patented technology for dynamic keyboards and methods for dynamically redefining keys on a keyboard in the context of Augmentative and Alternative Communication ('AAC') systems," said the complaint. (You can read the central patents here.) It further claimed that LoStracco and Collender had built their tools after attending "various seminars hosted by Semantic and PRC."

Speak for Yourself retorted in court fillings that the patents described a system that didn't work as well as it might—and which Speak for Yourself had improved upon. While PRC/Semantic relied on "polysemous" icons (icons with multiple meanings), LoStracco and Collender said that they built an updated system because "Plaintiffs’ icons were assigned many meanings, there are multiple ways to say the same word, and the sequences often required too many moves." Besides, they said, PRC/Semantic didn't even offer an iPad app.

So far, this was par for the course, and a set of lengthy court proceedings would be expected before anything might happen to the Speak for Yourself app; PRC/Semantic had not asked the judge for any sort of injunction that would have forced the app out of the App Store while they litigated the case.

But PRC/Semantic did go directly to Apple, and it got what it wanted without involving a judge at all.

The benign dictator of the App Store

On March 19, three weeks after filing the lawsuit, the two companies forwarded a copy of their patent complaint to Apple along with a request that Speak for Yourself "be withdrawn from sales, distribution, and downloading."

Apple's Terms of Service clearly give it the right to do any of these things. For instance, Apple gives itself "the right, but not the obligation, to monitor any materials submitted by you" and to "investigate any reported or apparent violation of this Agreement, and to take any action that Apple in its sole discretion deems appropriate."

In this case, Apple didn't act immediately. Someone from the App Store reached out to Speak for Yourself two days later, forwarding the PRC/Semantic demand letter and asking for written assurance that Speak for Yourself did not infringe on their rights.

On March 26, Speak for Yourself's lawyer provided such assurances. Apple said nothing further; the matter was presumed closed.

On June 4, however, the app disappeared from the App Store. Apparently without the developers' knowledge, Apple had reached out to PRC/Semantic once more, asking about the status of the lawsuit; finding that the case had not yet been settled, Apple decided to pull the app.

On June 5, after learning what had happened, Speak for Yourself demanded that PRC/Semantic lawyers withdraw their demand letter to Apple; they refused. Speak for Yourself then went back to the judge and asked for an emergency hearing "to prevent destruction of business."

"Apple's decision, which was prompted solely by the tortious interference of Semantic and PRC, fundamentally upended the status quo in a way that was never sought in this Court," wrote Speak for Yourself, "and as a result, did not afford SFY the proper procedural protections of a Court process or hearing."

The developers got their hearing before the judge on June 8, by phone—but the judge orally denied their request for a temporary restraining order against PRC/Semantic. The court documents do not provide the reasoning for the decision, and neither party would offer comment on the court case itself to Ars.

So, with legal options temporarily stalled, the battle for Speak for Yourself went public.

reader comments

155