During this years GNOME conference GUADEC Andreas Proschofsky had the chance to conduct the following interview with GNOME designer William Jon McCann. It touches on a range of different Linux desktop related topics, like the current thinking about a dedicated GNOME OS, all the ongoing criticism in regards to GNOME3 and which form-factors are the most important ones to GNOME.

derStandard.at: Windows Vista was often cited as a (missed) "Window of opportunity" for the Linux desktop. At the moment it looks like Windows 8 could potentially alienate lots of current "classic" Microsoft users, do you see a new chance there?

William Jon McCann: I think every time there is a new version of Windows people will say that but I'm not entirely certain that it's actually true. Any time there is a new product that changes the marketplace and that people will have to adapt to some will use that as an opportunity to do something different.

For me personally - and I can't speak for my company or any of my colleagues - I'm not all that interested in switching people from Windows. I think that was an interesting problem probably 10 years ago, but I don't think we still have to encourage people to leave Windows, it's just going to happen over time. People are moving to other devices - they are just not as stuck to the desktop like they used to be.

Basically for many of the same reasons we wanted to do something different from GNOME2, people are finding new ways to interact with computers. Essentially we were designing GNOME2 to be the free software version of a desktop computer system. And at some point we took a step back and asked ourselves: Are the problems people are having still the same? And really they weren't. There now is a wider variety of form factors, different types of devices, different types of interaction models - people are interacting with online services as much or if not more than with local data. So there definitely are lots of possibilities out there.

derStandard.at: But what is GNOME's target market in the midst of all of that?

William Jon McCann: Well we have existing partners that are actually using GNOME to make money, to serve their own customers. GNOME doesn't really have customers directly - and that's at the center of one of the ongoing discussion in the project right now. Why don't we have customers directly? Why do we have to have this distance between us? And I think a lot of people would like that to be a lot closer.

derStandard.at: So you agree with that?

William Jon McCann: I do. I don't expect that we do this alone without the partners we have - or without new partners - but I think we need to find a way to be able to reach a huge population that we could have never reached before.

A lot of the Windows users we have been talking about, that could be potentially interested in our stuff, I don't know if they even have a way to get GNOME. So why aren't there devices out there shipping GNOME? Which would be the most natural way to deliver our software.

derStandard.at: Apple and Microsoft seem to view the future in some sort of convergance between the mobile and the desktop space. So: What is primary target device for GNOME? Is it still the workstation, are we looking at a tablet future or is it a mix of both?

William Jon McCann: Unfortunately I don't think we get to choose, some of the bigger companies define the hardware platforms. We've always been following what the industry does, trying to get our software to run on whatever is out there. I would love to see free software on every possible device. But I think there are limits to what we can actually do with GNOME.

Our main target for GNOME3 is laptop use, which I think is by far the overwhelming majority of computing use today - in the non-mobile space. The second target is existing high-performance workstations. We've got a lot of criticism that we would not be interested in those, but as it turns out a lot of us still use them, so we are very interested in making those work perfectly.

A more aspirational goal is to be able to reach tablet-sized form factors. And part of the reason for that is a good number of laptops already do that, they are convertible into tablets. And basically we don't want to fail embarrassingly on those - as we do today. So we need kind of a hybrid approach, being able to do high-precision targeting and laptop use to the best of our ability and to have some capabilities for touch devices.

derStandard.at: During the conference the term "GNOME OS" was used quite a few times. What would you envision such a GNOME OS to be? Just a way to deliver GNOME to developers? A reference distribution? Or a full-blown operating system?

William Jon McCann: My definition of operating systems is basically two things: It's a well defined user experience and it's a well defined developer experience. So those are the two interfaces we need to provide and everything else is an implementation detail - down to the hardware.

I don't know if you saw Lennart's talk the other day, he said that we should let the user experience and the developer experience drive everything in the lower level stacks. So developers agree with that and it is not just designers making stuff up.

derStandard.at: But the question is: How to deliver all of that to the users? Ubuntu has its own distribution for instance, GNOME has to rely on others...

William Jon McCann: Exactly. And it's not only difficult for our users to get, it's also difficult for our developers. My primary interest right now is being able to validate our design decisions, being able to validate code commits. We need something to test, to find out if we break things. So if you go down that line of thinking - What are we making? What are we testing? What are we

delivering to our partners? - there is no other name than operating system for it.

derStandard.at: Still this is a developer system you are talking about. Do you think it might be interesting in the long run to also target "regular" users?

William Jon McCann: My goal is to put free software into the hands of basically everybody on the planet. So if we really believe in free software we have to believe that everyone has the right to it. Not just developers, not just currently active users. And we are really trying to do something about it. The designs that we do target potentially everyone. But on how to deliver it to users - this is something the whole community has to discuss and decide on.

derStandard.at: There are a lot of different proposals being made at GUADEC, but one thing seems to be pretty unclear to me: Who is ultimately going to decide which path to take?

William Jon McCann: This is a really good question, but there is no clear answer in open source or open communities in general. But as with probably pretty much everything the first steps are experimenting and just doing things. And probably in the end the right answers will prevail, the people doing the right things will prevail. But as far as who is going to make such a decision - I don't know. But if people are interested in something they will move forward with it regardless. And even though there might be some people who critique those ideas circulating, I really haven't heard any alternatives yet.

derStandard.at: Until now GNOME3 was "only" delivered as part of community distributions, next year RHEL 7 is supposed to be released. Is GNOME3 ready for the Enterprise Desktop use case?

William Jon McCann: I do think it's ready, yes. In fact we have been adding enterprise features all along. For GNOME 3.6 we are adding enterprise login support, so you can login to your desktop with your kerberos authentication, you can login to your domain. We are fleshing out the internationalization support that you need for a serious product like that, with iBus going in.

derStandard.at: Red Hat developer Benjamin Otte posted a blog entry recently, basically stating that GNOME is losing contributors. Do you think there was some fallout from the GNOME3 change or is this attributed to other factors?

William Jon McCann: I look at things a bit differently. I walk around the conference and I'm absolutely amazed by the energy we are seeing in the GNOME community right now. I am more optimistic about GNOME than I've been in a long time.

I think there was a time when GNOME had kind of a crisis, we didn't know where we wanted to go, we were lacking goals and vision - that was the end of the GNOME2 cycle. So we pulled together and formed a vision where we want to go - and actually did something about it. And now we have been marching on that plan for quite some time.

I think there are some valid criticisms of how people are getting our software, but I really don't see a drop in contributions. If you look at the number of Google Summer of Code students and the quality of their work it's absolutely amazing. We have a lot of new contributors there and we are very excited about that. But what I do see is a drop in number of testers, especially during the development cycles. We have fewer people testing GNOME outside of the active contributors. And there are a number of reasons for that, but that's also why we have these discussions around making GNOME more easily testable.

derStandard.at: Is this a result of Canonical going a seperate path, because especially during test cycles Ubuntu was GNOME's main test base?

William Jon McCann: That is a significant part of it, yes, but it's not the only one. Even when Canonical was collaborating and not making its own operating system we should have been doing better in GNOME. Why should we wait on others to build packages and deliver them? The turnaround time is way too long.

But there is another benefit to doing something like GNOME OS: When I started getting involved in free software I came from the outside, I started using some of the enterprise products. And I saw things that I could help fix, mostly design issues so I did patches but I didn't know the right way to submit them. So I sent patches to an enterprise's downstream bug tracker, but it turns out that's basically worthless. Because that package in an enterprise release is years away from the current source code. Then I figured out that you have to go to the community version of the enterprise product, but it turns out that's maybe not years but weeks and months too late. From there to getting things upstream - there is this huge divide. How do you get upstream? And for us, as a project, the question is: How do we get that person involved when she wants to?

derStandard.at: So you hope to also get more contributors into the project through GNOME OS?

William Jon McCann: Absolutely. We have that huge chasm between where the users are and where the development happens.

derStandard.at: In your talk you mentioned doing a Software Development Kit (SDK) and a new release of the Human Interface Guidelines (HIG), what are your goals there?

William Jon McCann: Well application development for GNOME is incredibly hard right now. But that's where the energy should be, and that's where the variety should be, where the choice should be. Historically we've had so much choice in the operating system level. If you wanted your computer to do something different, it was like "add an option", "add a mode", "add an extension or plugin or an applet" - and that's completely the wrong way to do it, in my opinion. It comes at the expense of having any kind of application story.

It's kind of ironic if you think about it: If you limit the choice particularly in the APIs you provide you exponentially expand the choice in the applications you have - they are completely in indirect proportion. And I think that's really what we want to see, we want to see way more applications and way more users.

derStandard.at: Wouldn't that also mean, that distributions should rethink what their role actually is in the Linux world? On which levels they differentiate?

William Jon McCann: Absolutely. They might even want to rethink why they have to differentiate at all, what their specific purpose is. And if they are just there to spread free software I think we should ask ourselves: Is it more effective to have it the way it was or could we join forces and do it better? Is the application story easier to write if there is one application store, if there is one app that you can install on anything that implements the GNOME OS? Or is it better to have third party application authors writing for 20 different distros? Which one would they do? Which one COULD they do?

I think it's fairly obvious when you look at it, why we have basically no applications for Linux - it is impossible. It's impossible to write an application that runs consistently on even two or three distros. And that's only in the current release. If you want to support something that runs essentially forever without having to uninstall it every three or six or twelve months you are completely out of luck.

derStandard.at: This would essentially boil down to having something like a core OS for everyone, which you could then define as stable?

William Jon McCann: The discussions are still ongoing, so this has yet to be decided in any way, but I think that's a pretty good idea. What seems to work in other systems - I think it makes sense to define some things that are stable and could be shared between applications and then have some certain private APIs that the operating system only could use. But anything beyond that the application should find its own way to do.

derStandard.at: In GNOME 3.6 the file manager has been redesigned quite significantly, adding a stronger focus but also dropping some functionality, which already got some pretty strong reactions from the community...

William Jon McCann: I don't think this will be the same once the final version comes out, you have to realize what people are seeing right now are very, very unstable releases and the story is nowhere near complete...

derStandard.at:...but for instance there seem to be a whole bunch of strong opinions against the removal of the split view.

William Jon McCann: It's always hard to gauge how many people are really using it from the responses. The people who did use it obviously felt pretty strongly about it - that's what we know, and I can't argue with that. But it always was a pretty impossible feature to find if you didn't know that it is there. Before I looked into it I was always wondering why Nautilus had these empty "Copy To" and "Move To" submenus unless you were using an extra pane - which was really weird.

derStandard.at: What I was trying to get to: If the long term goal is to get rid of the file manager and use specialized apps like Documents or Videos for content discovery, why not keep the file manager as a power user tool?

William Jon McCann: Well it is. But there are few things to note right now. We don't have all of our applications ready right now, Music and Photos for instance are still missing. So this puts us in the position of how do you find things in the overview if they aren't provided by these applications? Conceptually, the way it is supposed to work is that if I type in a name the photos app should display all the results it knows about or the music app will come up with an artist that I type in. But as we don't have those applications - who is going to provide those results? And I guess the natural answer is "Files".

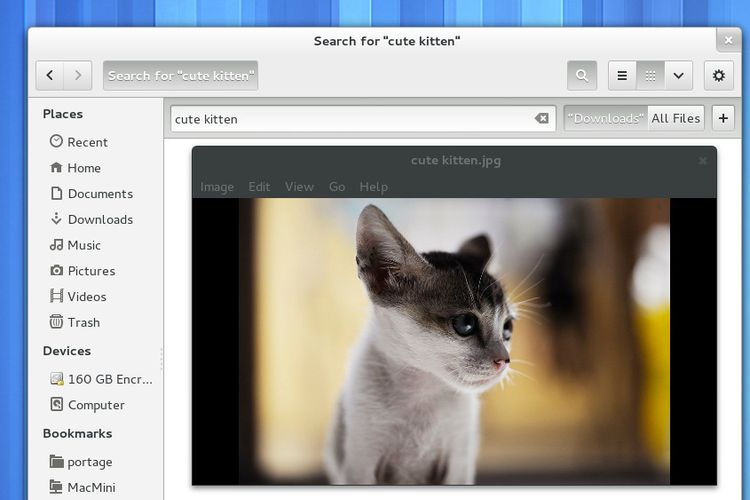

But we have a problem there because Files had completely broken search functionality. It could either work with Tracker [GNOME's search system] - or not, and that was decided at compile time. Tracker indexes only a very small set of your files, if it wasn't in that indexed set, it would return no results. And if wasn't compiled with Tracker it would do this manual filesystem search which could take many, many minutes. Basically there was no provision for how we handle removable devices. So long story short: It's completely broken. And that's one of the main things we want to fix, making the file manager effective for actually finding files. Which it wasn't. It was ok for dragging and dropping files around, but that's not enough.

derStandard.at: Isn't that a bit like reinventing desktop search?

William Jon McCann: I don't think it is reinventing anything. I can't name any file manager these days that doesn't have an effective search function. That would be crazy - but that's what we had.

So that's the first thing we have to make work. Another thing is to make it easier to manipulate files. We've added things like being able to select a group of files and making a folder out of them. And we now have a way to take files and move them to someplace explicitly. Up until now, we used this very odd mental model of copying files into some strange place called the clipboard and then paste them somewhere later. We had bug report after bug report of how Copy and Paste really confused people when it came to files. So we added an explicit way to copy and move files, you select some files, choose move and it asks you where. And this has some relation to extra pane, because this is basically an extra pane on demand. You get a file chooser that lets you put anything anywhere you want, you don't have to have another location already open. So it's very quick, you don't need to pre-setup your windows and I think it's a lot more effective.

Another change that we've made is showing recent files by default. Before, Nautilus would just open with your home directory, which was sort of the best guess we could come up with for what you might be interested in. But most likely the stuff you are looking for is somewhere else, in a subfolder, on an external drive. So we thought a better place to start with the file manager is a list of your recent files.

And this list goes on and on. So essentially we removed one or two things to make room for dozens of new features. And a lot of those are actually responding to bugs that have been open for years. There is not a lot of stuff that people didn't ask for that we are getting in.

derStandard.at: In a recent interview Mark Shuttlworth said that they (Canonical) really had to push hard through all the criticism they got for introducing Unity, otherwise they wouldn't have been able to realize their vision. I guess you would say the same about GNOME3....

William Jon McCann: I think what we are experiencing is actually quite different from what they are experiencing which is in some ways is pretty ironic. We work as a community, we do everything in the open, this is in stark contrast to the way Canonical works. There are good and bad sides to that. The people who want to be involved with GNOME can be involved in even the earliest conversations we have. But they can also be involved in the very earliest complaints about something - it just depends on what sort of person they are. When you see the guts of the process you can pick up on a mockup that goes into a git repository - and even thought it's just an experiment it suddenly becomes an article and people are flaming it like: "Look what they are doing!" Or people pick on a very, very early development release of the file manager. If we worked like Canonical we would only put out things that are finished and have a press release to handle the whole situation - that's a completely different way of working.

derStandard.at: Is the free software world a hostile place for change?

William Jon McCann: The free software world to me is the same as the world. I think you will always hear more from people that don't like something than from people who do. And I think that's one thing that people who are reporting on GNOME3 haven't taken into account - that there are actually a lot of people who love it. But if you love something and it just works, it's part of your daily life and you don't feel the need to talk about it all the time.

But we do need to listen to people who aren't happy with what we are doing, and try to figure out what the actual problems are they are experiencing. And if you are trying to do this, you tend to ignore the tone, the rudeness that comes with it sometimes.

derStandard.at: Do you get used to this after some time?

William Jon McCann: I personally read just about everything anybody has ever written about GNOME. I do it every single morning, directly after I wake up, I have saved searches in all the online media, all the social media, all the mailing lists. And I read all of them, basically as an exercise to extract data from them to inform my opinions. But I don't think you can get used to the way people sometimes say things.

(Andreas Proschofsky, derStandard.at, 19.08.12)