MARSHALL, TEXAS—The slide that defense lawyers showed to the jury read: “This isn’t new.” In a patent case, it could have been a smoking gun—after all, it was written by the inventors themselves. They were describing their business, Nexchange, to a San Francisco conference back in 2000; it was three years before they received their first patent and turned their focus to litigation.

But hours later, inventor Daniel “Del” Ross Jr. was on the stand, and he seemed none too concerned that the crux of his idea was old—if not ancient. He had a patent, twice reviewed by the US Patent Office, and a simple story to tell: “The big difference is, we invented this for the Internet,” he told the jury.

Even though Nexchange failed in the marketplace—and is in fact suing a competitor, Digital River, that survived it—the founders are resolute in their belief that their invention was special.

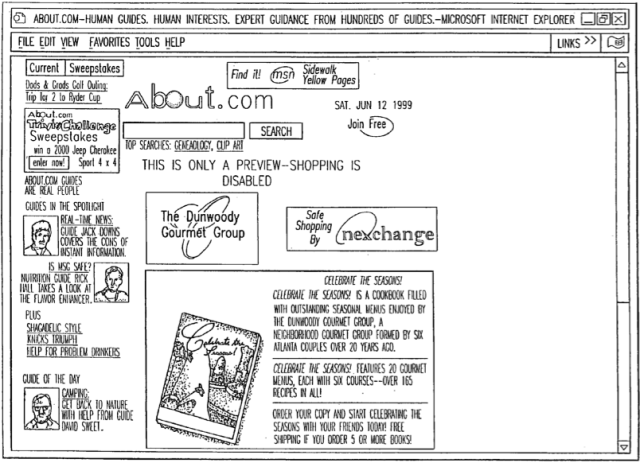

Nexchange’s idea was to help online retailers get more business by connecting their stores directly to popular content sites like CNN.com; after all, that’s where the users of the still-young Web were hanging out. Their system built e-commerce right into “host” sites like CNN. A merchant could place their product on the host site, and would only have to pay when a sale was made; the host site, in turn, didn't need to worry about losing its readers to another website. It was an early version of online "affiliate marketing," which has become an increasingly common system for online selling—affiliate marketing is expected to be a $4.1 billion industry by 2014.

While affiliate marketing has thrived in e-commerce, the basics really aren’t new, as the Nexchange slide noted. In fact, the 2000 presentation went on to point out that the Nexchange affiliate marketing system wasn’t all that different from putting “McDonald’s in Walmart.” And as company co-founder Ross Jr. would admit to the jury later that morning, the simple idea of going where the customers are is older than Walmart; it dates at least as far back as the first person who repeated the old sales mantra “Location, location, location.”

“If we could do the same thing for the Internet, and put an online store in the right location, we could do a lot of good and sell a lot of products and services,” Ross said on the stand Monday morning. Taking the defense’s argument and running with it, he admitted that putting McDonald’s in Walmart was, in fact, a great idea. “That's kind of what we were doing,” he said. “We were doing it on the Internet, which was new.”

Even that is hotly disputed, though. One of the defendant companies at this trial, Digital River, was embedding online stores on websites back in 1996—a full two years before Nexchange was founded and filed its first patent application. Ross and other plaintiffs’ witnesses say Digital River just couldn’t get the “look and feel” of its client sites down correctly in the way that their system did.

Wielding that argument, and a team of talented lawyers, Ross and his father, Danny Ross Sr., have managed to put most of the online travel industry—which relies heavily on affiliate marketing systems—on the ropes. Once Nexchange failed, the Rosses formed a patent-holding company, DDR Holdings, that bought up the Nexchange patent applications. Once the first patent was issued, they started sending out threatening letters to e-commerce companies. In 2006, they sued nine companies, including big online travel players like Expedia, Travelocity, and Orbitz.

The suit was delayed by a lengthy patent reexamination, which DDR underwent voluntarily after defendants brought out their prior art. But the patents survived and were confirmed by the US Patent Office; the key patent in this suit is No. 6,993,572, the second of three issued to DDR.

Now Expedia, Travelocity, and several smaller travel companies have all paid undisclosed settlements for their patents. The final two defendants, Digital River and World Travel Holdings (or WTH), have opted instead to face an East Texas jury trial, now underway in the small town of Marshall.

DDR is demanding a 5.5 percent royalty on the two companies’ affiliate marketing revenue. For Digital River, that’s a bit more than $10 million for the period in question, and it's about $6 million for WTH, a smaller company that specializes in booking cruises online. The numbers aren’t huge by the standards of modern patent warfare, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t burdensome. In the case of WTH, a $6 million verdict would be more than twice the profits it has made in the affiliate marketing business during the entire damages period, which goes from 2006 to mid-2012.

If DDR wins, more lawsuits are likely to follow. The biggest companies on the Internet are involved in affiliate marketing now. And the company is ready to sue outside that market, too; Digital River is an e-commerce company that mostly helps software companies like Microsoft and VMWare run their online stores.

The DDR case shows clearly why, for those who want to battle software patents, it’s a major uphill battle. An unsuccessful company was able to transform itself into a patent company—the kind of company often derided in Silicon Valley as a "patent troll"—and force other companies, even one operating well before it was, to trial.

Nexchange took on heaps of venture capital, growing to about 100 employees, but never turned a profit. Years later, the company’s founders have been able to come back and sue the industry players who did survive, claiming they invented the system first and others came later. Even assuming that’s true—and the claim is hotly contested by the defendants in this case—is it good policy to give a long patent monopoly to one player in a fast-changing field? Especially a player that is no longer even in the market?

reader comments

86