Plenty of industry heavyweights were active at the Mobile World Congress (MWC) last week, but there was a very noticeable, major absence: Google. The company's invisibility in Barcelona was a microcosm for perhaps the biggest trend coming out of the conference: co-option—companies seemingly adopting existing brands as their own.

Sure, Intel (keen to promote the Android compatibility of its new Clover Trail Plus platform) proudly showcased its Google partnership. The company had various poor souls dressed as green robots with Intel Inside badges. The company even had some at the Barcelona airport, and an alarming number of conference attendees were keen to have their photo taken with the robot.

But everyone else? Their smartphones may have been running Android, but you'd never know it. "Android" isn't a feature. It's barely even a footnote. The identity of these phones is Samsung, HTC, Sony, LG—not Android. Google's invisibility from MWC mirrored Android's invisibility from the handsets.

Google hasn't exactly helped promote the Android brand, with its (in some ways) competing "Nexus" and "Play" brands, but it's no wonder that Google is reported to be fearful of Samsung's dominance. It's arguably not a problem that Google should ignore, either, as it's impeding Google's ability to improve the platform. For example, Google long ago switched to a new button layout (from left-to-right: back/home/multitasking), but Samsung's devices stick with the old one (menu/home/back), which is less convenient and meshes poorly with new applications. It wouldn't be the least bit surprising if Samsung stuck with the old layout in the Galaxy S IV.

Nokia too is co-opting a brand, though this time it's the Windows Phone brand. It does get some mention, but as we've noted before, "Lumia" is the brand with name recognition, not "Windows Phone." In Microsoft's case, the tight control of the underlying platform precludes the kind of inconsistency and inconvenience that afflicts Android, so it's less of an immediate concern. It could prove troublesome in the long term, however, as it makes it that much harder for other companies, such as HTC, to bring Windows Phone devices to market.

There’s no obvious way for Google to reclaim Android.

To these, we now have Ubuntu from Canonical and Firefox OS from Mozilla to add into the mix. Both open source operating systems were on display, with Mozilla boasting a number of design wins for its HTML5-driven platform. Being open source—and likely more open than Android, which is substantially developed in private before a source drop is dumped on an unsuspecting world each time a new version is released—puts these platforms at the same risk.

Although both Mozilla and Canonical protect their trademarks in various ways, it would seem relatively straightforward for someone to take either platform, slap on their own name and branding, and call it their own (similar to the way Ubuntu already co-opts Debian). We asked Mark Shuttleworth, CEO of Canonical, and Mitchell Baker, chair of the Mozilla foundation, what they would do to prevent this. Both argued that, essentially, being co-opted was fine. It's all in the spirit of open source.

The problem is that third parties could develop the platforms in undesirable ways. For example, native applications could be grafted onto Firefox OS, undermining its HTML5 concept. Firefox OS is Mozilla's hedge against the rise of the app and the marginalization of the Web: someone slapping native apps onto it would be a big blow.

While MWC's path back to its roots is clear and the transformation seems to be under way already, there's no obvious way for Google to reclaim Android. A stable of strong Motorola handsets might enable the company to push things in that direction, but so far it has resisted doing even this. Motorola's handsets are not Nexus handsets. Come 2014, it would be no great surprise to find the last vestiges of the Android name gone forever.

Endangered at MWC: Flagship releases

In one form or another, Mobile World Congress has been around for more than a quarter of a century.

In theory, it's a giant trade show organized by the GSM Association, a group of 800 mobile operators and more than 200 handset makers, network hardware companies, and media companies. The event is designed so that these entities can get together, hawk their wares to each other, and trade views on the state of the industry. It's for people in the business to talk to their peers from around the world.

As with another big trade show, CES, MWC has become something more than that. With the rise of the smartphone in particular, the event has been used to announce important products not just to people in the industry but to the mainstream media as a whole. This has tended to overshadow the other aspects of the show, at least as far as press coverage goes.

For example, at the show last year, Nokia unveiled the 41MP 808 PureView and a world edition of the Lumia 900. Samsung used the 2011 event to officially unveil the Galaxy S II. The same year, LG announced the Optimus 3D, a device that was, for a time, the company's flagship.

This year things were a little different. HTC decided to launch the HTC One at a press conference the week before the event. LG likewise announced the Optimus G Pro the week before MWC. Samsung went one better, announcing on the first day of MWC—but not at MWC—that its Galaxy S IV event would take place mid-March in New York City.

Nokia did announce some new phones, but not the high-end flagship some were hoping for. Rather, the company revealed a pair of Windows Phone 8 handsets, one mid-range, one low-end, and a pair of feature phones for emerging markets.

This too is similar to what we've seen at CES. Microsoft announced in late 2011 that CES 2012 would be the last time the software giant gave the opening keynote presentation. Redmond said that CES was a poor fit for its release schedule, so splurging on a big presence wasn't worthwhile.

Sony announced the PlayStation 4 at its own event, not CES. Microsoft is expected to have its own Xbox "Next" event in April instead of piggybacking off E3 in June. Apple, of course, launches all its products at its own events and never bothers with these industry shows.

Signs are that MWC is going to evolve in the same way. It will be important for the industry and important for companies without the name recognition that the likes of Samsung and Motorola have. But what it won't be is a major launch event for major products.

There was some hedging of bets by some attendees. Samsung did launch a device at MWC (or at least, the day before MWC), with the Galaxy Note 8. Sony announced its slimline Xperia Tablet Z. HP followed Samsung, announcing its Slate 7 the day before MWC started. Clearly, being part of the MWC news cycle was still seen as desirable for these smaller announcements.

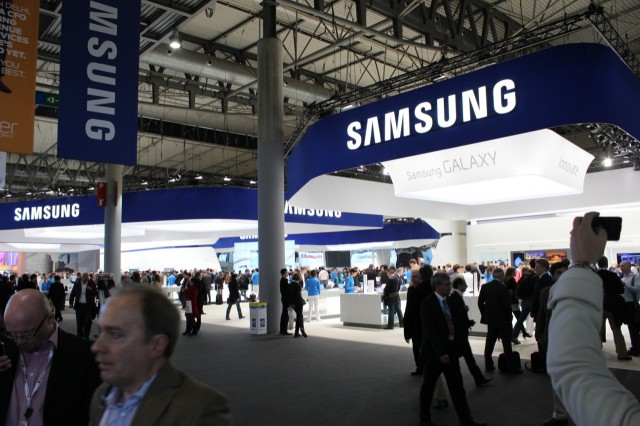

At MWC itself, Samsung, LG, HTC, Motorola, and Nokia all had substantial stands, as did companies trying to enter the European and North American consciousness such as Huawei. Their stands were all furnished with dozens of their new devices (with the exception of HP's stand; for reasons that escape me, the Slate 7 seemed to be AWOL save for a unit locked away in a display case). If you're a major phone builder, being seen at MWC still matters.

Strikingly absent were Microsoft, BlackBerry (née RIM), and Google. Microsoft and RIM had both booked hotels for their own private events. Microsoft had nothing to say, and BlackBerry launched its new operating system and phones just a few weeks ago.

This is probably the future of MWC. It's the future of CES, too. Both events will return to their trade show roots, with mainstream news taking place elsewhere.

reader comments

78