The US Supreme Court issued rulings this morning in two of the five patent cases it heard this term. In both cases, the high court unanimously struck down rules created by the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, the nation's top patent court.

The two rulings continue a pattern that has developed over the past several years, in which the Supreme Court has overturned key Federal Circuit rulings, finding them too favorable to patent-holders and too harsh on parties accused of infringement.

All four of the companies involved in today's opinion are competitors with real products—none represent the much-debated "patent trolls," that is, companies with no business beyond patent lawsuits. Yet, the issue of patent trolls looms large in the background of these opinions.Both decisions will make life easier for Internet and other tech companies frequently accused of infringement. In the case of Limelight Networks v. Akamai Technologies, trolls were happy to use the Federal Circuit-approved theory about "induced infringement" to sue tech companies. They argued that even when a defendant didn't complete all steps of a patent itself, it encouraged its customers to do so.

In the case of Nautilus v. Biosig Instruments, the Supreme Court has made it easier to throw out patents on the grounds that they're "indefinite." The ruling widens another path of attack that can be used against vague patents.

Limelight v. Akamai

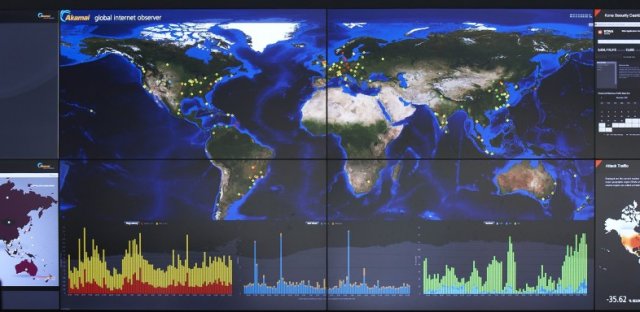

Akamai controls about 75 percent of the market for Internet Content Delivery Networks, or CDNs. In 2006, it sued a much smaller competitor, Limelight Networks, for patent infringement.

Limelight was found liable by a jury, but won its case in post-trial motions. On appeal, the Federal Circuit sat en banc, and in 2012 the court voted six to five that Limelight would need to face litigation again, even though it didn't perform all the steps of any Akamai patents. Because Limelight told its customers how to perform certain parts of the patented process, including the step of "tagging" content to be moved out over CDNs, it could be liable for "inducing" infringement of Akamai's patents even if it didn't infringe itself.

The result was good for patent-holders, particularly in computer and software technology, and hard on defendants. Often, patents describing processes taking place on the Internet can't pin all the steps on one party. When they're allowed to consider both what a web-based service does, and what its users do, that makes it easier to find infringers.

As an example, take TQP Development, a patent-holding company that went to trial against Newegg after suing hundreds of websites for using a common web encryption scheme. The company was able to push ahead with its case even though it admitted Newegg didn't perform all the steps of its patent, because it accused Newegg users of fulfilling the other steps.

Those types of cases are why a broad range of tech companies urged the Supreme Court to side with Limelight, which it now has.

Hunting for inducement? Just find infringement

In a strongly worded opinion [PDF] written by Justice Samuel Alito, the Supreme Court suggests that the Federal Circuit's analysis "fundamentally misunderstands what it means to infringe a method patent."

"A method patent claims a number of steps," writes Alito. "[U]nder this Court’s case law, the patent is not infringed unless all the steps are carried out."

In order for there to be a trial on inducement, the high court ruled, there has to be infringement in the first place. Under the precedent created by another Federal Circuit case, called Muniauction, that means one party must fulfill all steps of the patent.

Alito's opinion acknowledges the fact that in some situations, would-be infringers could "evade liability by dividing performance of a method patent’s steps with another whom the defendant neither directs nor controls." But to the extent that problem exists, it's because of Federal Circuit rules created in Muniauction.

The Supreme Court specifically declined to reconsider that case, but the case now goes back down to the Federal Circuit, which could broaden the "direct infringement" rules of Muniauction if it wishes.

Dennis Crouch, a University of Missouri School of Law professor who writes the popular Patently-O blog, called the opinion "harsh toward the Federal Circuit, but somewhat poorly written." He notes one passage that suggests the Supreme Court believed that the Federal Circuit allowed for "inducement" to be found even when "fewer than all of a method's steps have been performed," which was never the case.

Nautilus v. Biosig: Seeking “reasonable certainty”

In the second case decided today, Nautilus v. Biosig, the Supreme Court tightened up the rules for how specific or "definite" the claims of a patent must be.

Section 112 of US patent law requires inventions to be described in "full, clear, concise, and exact terms," so that any person "skilled in the art" could create the invention. Patent claims are defined by federal judges during a process called "claim construction," a key part of any patent lawsuit.

Under the Federal Circuit rules in force until today, judges were supposed to proceed with claim construction in almost every circumstance. They could only throw out a patent as indefinite if a claim was found to be "insolubly ambiguous."

That essentially invited judges to go ahead and give meaning to a patent that was otherwise written so badly it couldn't be understood.

Tolerating such "imprecision" hurts the public-notice function of patents, which are supposed to be public documents letting everyone know which inventions are in the public domain, and which must be licensed or purchased from patent holders.

Loose rules could "foster the innovation-discouraging 'zone of uncertainty,'" the court held, in a unanimous opinion [PDF] written by Justice Ruth Ginsburg.

Instead, judges should find patents invalid when they "fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention."

"Absent a meaningful definiteness check, we are told, patent applicants face powerful incentives to inject ambiguity into their claims," wrote Ginsburg.

The case originated when Biosig sued Nautilus, a maker of exercise equipment, over its patent describing a heart-rate monitor with a "spaced relationship" between the electrodes. Nautilus lawyers denounced the phrasing as "gibberish," meaningless since it didn't say how big the space was. After the Supreme Court agreed to take the case, tech companies and public interest groups pounced on Biosig's claims as a poster child for vague patents.

Imagine, said Public Knowledge and the Electronic Frontier Foundation in their brief on the case, if language like "spaced relationship" were to be used in a land dispute regarding how far from a highway a hotel should be erected.

"'Spaced relationship' could mean a foot from the highway, or a yard, or a mile," stated the groups. "The developer could guess at the meaning, but a wrong guess could render the entire investment in building the hotel a waste."

With the opinions issued today, the Supreme Court has now decided four out of the five patent cases it heard this term. In two earlier cases, Octane Fitness v. Icon Health and Highmark v. Allcare, the high court made it easier for patent defendants to collect legal fees when they win lawsuits.

The one case not yet decided, Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank, is the most closely watched one. It relates to when software claims are too "abstract" to be patented, an issue that was not resolved even after the 2010 Bilski decision.

reader comments

55