It’s been exactly ten years since the launch of OpenStreetMap, the largest crowd-sourced mapping project on the Internet. The project was founded by Steve Coast when he was still a student.

It took a few years for the idea of OpenStreetMap to catch on, but today, it’s among the most heavily used sources for mapping data and the project is still going strong, with new and improved data added to it every day by volunteers as well as businesses that see the value in an open project like this.

To celebrate the project’s birthday, I sat down with Coast, who now works at Telenav, to talk about OpenStreetMap’s earliest days and its future. Here is a (lightly edited) transcript of the interview:

How did the project get started?

Image credit: Steve Coast

So the original idea was way simple. I had a GPS unit attached to my laptop and there wasn’t very much you could do with it because there wasn’t any data. You could download a picture of a map, but if you wanted to do anything like have the computer figure out what roads you were on or do turn-by-turn navigation or anything that’s kind of useful, you couldn’t do it because there wasn’t any map data. So I just thought: why don’t we create some map data? When you have a GPS, you can just drive or bike or walk around all the streets, all the roads, all the footpaths and use that information to create a map. I build a little bit of the map where I live and you build a little bit of where you live and we build this thing like a jigsaw puzzle — and incidentally give it away for free. Just like Wikipedia was building an encyclopedia in a very similar way, I copied many of the ways Wikipedia was built with — like open licensing, the ability for anybody to contribute and so on.

What were you doing at the time when you started the project?

I was working at the computer laboratory in Cambridge. I did a lot of stuff and most of it didn’t work out.

But OpenStreetMap did. How did you get others to join the project?

Well, there’s a couple of ways. One is just PR. I gave a lot of talks. Linux user groups used to be very popular — people getting together on a Saturday afternoon to talk about Linux. They already knew half the story because they knew about open source and they knew about computers and data. So it wasn’t too hard to explain what OpenStreetMap was doing. From there I gave talks at mapping conferences. I stopped counting at something like 500 talks. I used to use the number on my first slide.

Was it pretty much just yourself in the early days?

Yeah. Absolutely. And then we had some mailing lists and started to form a community. I also invented this thing called mapping parties, which were typically a weekend event. People would come along and we’d show them how to use a GPS because this was pre-iPhone. We’d walk around, collect data and show them how to upload it and integrate it to OpenStreetMap. And then we’d go to the pub afterwards. I really wanted to get people talking and make it feel like a community.

It took a while and you can’t convince everybody, but it got to the point where it was self-sustaining.

At what point did you know this was going to take off?

Ha. I’m not sure I do. I look at it really as a series of milestones, right? We are still not quite there. I mean, OpenStreetMap is a great display map, but there is still not a whole lot of navigation data and address information, for example.

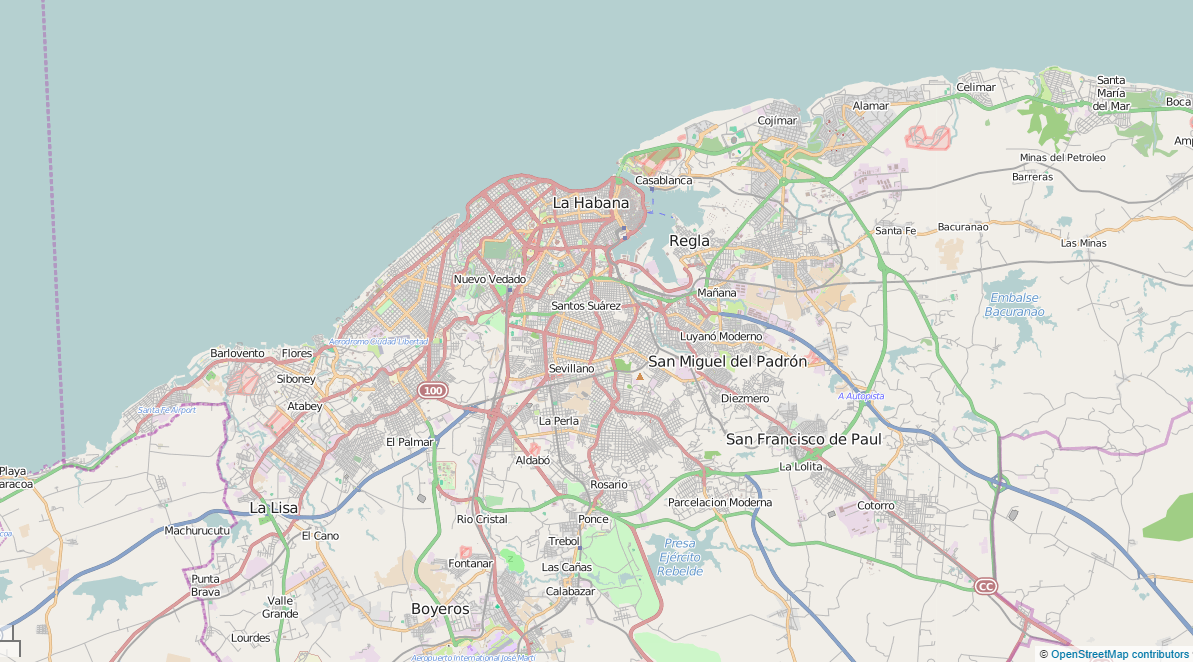

But I can still remember when I stopped being surprised, and that was when I was at a mapping party. To show people the power of the project, I’d ask them to pick a place that was important or interesting to you. And then on OpenStreetMap, we’d zoom in to what was interesting to them. Then I’d ask them to tell me if they saw any mistakes or what was missing — and then we’d edit it. That made it very personal and showed the power of the map. And typically they’d say there’s a road missing or something and we’d edit the data. There was this particular time when somebody said “let’s zoom in on Cuba.” At the time I thought the UK would be great, Spain had a bunch of information but if we zoom in on Cuba, there would be nothing there. So we zoom in over Havana and it was basically complete. All the roads, one-way streets. That’s when things stopped surprising me. That was around 2008.

Did managing the infrastructure get harder as more people started using the service?

There are a couple of ways to look at this. It was less of a technology problem than it was doing things that other people didn’t want to do and getting people involved. I had a bunch of experience running large SQL databases and doing large SQL queries.

There were other people who were trying to do open mapping, but they maybe two mistakes. One is they concentrated on the shiny stuff: the editor and the website and so on. I focused on making the backend work. That wasn’t quite as much fun to work on. The other projects also wanted to limit you in some ways. They’d say you can map whatever you want, but it has to be in England, or it has to be footpaths. What we did was say: hey, it’s open source for everything. That made it relevant to everyone.

But in terms of the technology itself, initially I wrote the whole thing in Java and it was talking XML-RPC. But around that time, REST was becoming popular and it was becoming obvious to me that it was going to win. Java was also becoming increasingly painful. That’s when I switched the whole thing to Ruby. And then about that time was when Ruby on Rails started, so I switched to that. It was a fairly early project to use Rails.

What about financing the project? How did you do that?

The costs were actually very low. There were a couple of computers and bandwidth that was needed. There wasn’t actually a lot of infrastructure that was needed. I just convinced the university to host it and at the university where I was [University College of London at that time], they had great Internet connectivity. So the cost were actually pretty minimal. But to answer your question more directly: the money that we did need would typically come from conferences. We’d run a conference and sell t-shirts and we could buy a couple of servers every now and then.

How did the arrival of smartphones change the project?

The early smartphones were pretty terrible, right? You could have something in your pocket to access the Internet, but the turning point was really the arrival of the iPhone. It replaced the five devices you used to carry around.

The short answer is that it lowered the cost of us collecting data and made it more accessible to everyone. But it also changed people’s perception of what a map was and how accessible a map should be to someone on the street. It also changed peoples’ relationship with maps. Instead of this static artifact, it was now something you’d always have with you. It made it malleable from this static artifact — and it turned it into something self-updating.

Maps used to be this stand-alone app for your PC — and then Apple and Google Maps changed it to this thing that was always with you. And now maps are just going into every application because you can make them relevant for everything.

Fiji’s Mana Island resort on OpenStreetMap.

What’s the state of online mapping in general today?

I think the challenge remains to open up the data. OpenStreetMap is focused on the data, not necessarily competing with Google. They have a lot more data, right? Anybody can go and make a nice mapping experience available on the web or on mobile, but the limiting factor is the data. Google made this huge investment in building its own data set. Opening up the data levels the playing field for everyone. Not necessarily for consumer experiences. It’s still hard to make something that’s delightful for your users. But if you don’t have the data, you don’t have the option for even trying that.

How is the ecosystem around OpenStreetMap doing?

We’ve got tile servers and people are doing that, but the reason I joined Telenav was to get navigation working.

We’ve had the ability to use OpenStreetMap as a display map for quite a while now. You look at it and it looks great, but it’s much harder to make it navigable. And that’s really what you need to make the end-run to the consumer experience. You have to be able to get from A to B.

Do you need a commercial partner for that?

It’s pretty hard to do. OpenStreetMap lacks a couple of things. Navigable information like one-way streets, time restrictions or speed limits. It also lacks address data. Telenav has a lot of GPS traces. We process all of those into navigable information. If you take all the people traveling on the freeway and they all go 55, you know that’s probably the speed limit. If nobody is turning left at an intersection, there is probably a turn restriction there.

So you can fix that with GPS traces. But the address data is harder. In the U.S. you can license this data, but in Europe and other places it’s much harder. In the U.S.. the federal government is mostly a public domain organization and that trickles down to the local governments. You can get data from that. Every other country tries to own all the mapping data. In the U.S., most of the address data is also very predictable. In the rest of the world it’s not that simple. In Japan, the street number is often based on the block and the age of the house. So the first house is number one, the second number two and so on. So it’s much harder to figure out where things are by inference.

It’s something that a lot of people want to solve, so I expect it will get fixed somehow and there are a bunch of interesting way to do this. You can crowdsource the data, you can pay people to go collect it, but I expect it’ll be a mixture of a number of things. Every time you use a check-in app, for example, you are signalling that this restaurant with this address is in this location.

What’s the relationship between OpenStreetMap and your employer Telenav now?

Telenav has hired a number of key people. One thing we do is we contribute our data back as much as possible. When we figure out a street is a one-way street, we have a process to contribute that back. We sponsor a website called MapRoulette, which is a crowdsourced game for contributing. We also sponsor the conferences and do various spot donations. For the 10th anniversary, there are parties around the U.S. and we are giving them gift cards to buy foods and drinks. That sort of thing.

How has the community around OpenStreetMap changed?

The raw numbers have gone up, but it’s also — in the beginning it was very much around open source ideology. “Data wants to be free” and so on. But as the project grew, it’s got much more diverse. There are lots of companies involved now that want to improve the mapping experience. There is a huge variety of people now involved that wasn’t there in the beginning — and that’s a good thing.

Looking forward, it sounds like address data and routing are the big challenges. Is that what you are mostly working on right now?

The address data is really the most important and interesting thing to work on. The routing stuff you can infer from GPS traces and there are many ways to do that. But if I had a solution for the address data I’d let you know, but we’re not there yet.

Do you remember what the first street on OpenStreetMap was?

That’s a good question. I’m not sure but I think it would be either the inner or outer circle of Regent Park in London.