Apple will soon have to face a trial over accusations it used digital rights management, or DRM, to unlawfully maintain a lead in the iPod market, a federal judge has ruled. The plaintiffs' lawyers, representing a class of consumers who bought iPods between 2006 and 2009, are asking for $350 million.

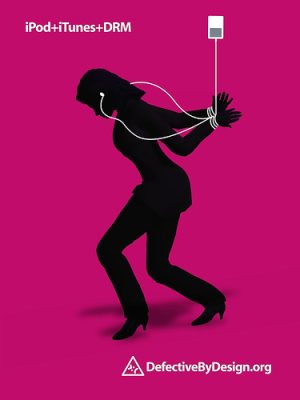

Last week, US District Judge Yvonne Gonzales Rogers gave the green light (PDF) to sending a long-running antitrust lawsuit against Apple to trial. Plaintiffs in the case say that Apple used its FairPlay DRM system to "lock in" its customers and make it costly to switch to technology built by competitors, like Real Networks. They describe how Apple kept updating iTunes to make sure songs bought from Real's competing digital music store couldn't be used on iPods. As a result of this lock-in, Apple was able to overcharge its customers to the tune of tens of millions of dollars.

At an earlier hearing, Apple's lawyer claimed the plaintiffs don't have "any evidence at all" showing harm to customers from the FairPlay DRM. The Robins Geller lawyers representing the class said they had thousands of complaints from consumers who were upset because they couldn't play non-iTunes songs on their iPods.

Now, the pressure will be on Apple to either strike a deal or face a team of lawyers looking to put a nine-figure damage demand in front of a jury. Trial is set for November 17 in Oakland, California.

Remember iPods?

The claims in the case harken back to a time when iPods and the iTunes music store were fast becoming the center of Apple's business. In 2004, Real Networks launched a new version of RealPlayer that competed with iTunes. Real made songs from its own digital music store mimic Apple's FairPlay system so that music bought from Real could play on iPods. They called the compatibility feature "Harmony."

In this lawsuit, plaintiffs are claiming the anti-Harmony measures in iTunes 7.0 broke antitrust laws, because it had the effect of illegally raising the price of iPods. Users were continually forced to either stop playing any songs they had bought from the Real store, or convert them to a non-DRM format, for example by burning the music to CD and then ripping the CD to their computer.

That produced "lock-in" to the iTunes environment and increased consumers' "switching costs," the plaintiffs argue.

Apple countered that there was no evidence its "pricing committee" even took Real or its Harmony system into account when it set iPod prices. It also noted that Real had less than 3 percent of the online music market in 2006, when Apple released iTunes 7.0

But that didn't persuade Gonzales Rogers to exclude a key expert's testimony, which is what Apple would have had to do to avoid this trial.

Dueling economic theories

Apple's lawyers tried to nix the trial by challenging the evidence brought forth by the plaintiffs' expert, a Stanford University economics professor named Roger Noll. But in her most recent order, Gonzales Rogers saw no reason to throw out Noll's opinions, which "derive from transactions supplied by Apple itself," she noted.

The iPod maker said that Noll's theories about overcharges weren't applicable to its policy of uniform pricing. "However, the record contains non-trivial evidence that the actual prices charged were not in fact uniform and that pricing decisions may have incorporated factors above and beyond Apple's preference for so-called "aesthetic" prices," wrote Gonzales Rogers.

The issue isn't whether Noll's opinions are correct, but whether they meet a legal threshold as admissible evidence, the judge stated. She found they did, as Noll's work is "the product of a generally accepted method for demonstrating both the fact and the amount of antitrust damages."

"We're delighted that we're finally able to present the case to a jury," class lawyer Bonny Sweeny told The Recorder, which reported on the ruling earlier this week. Apple didn't respond to a request for comment.

The litigation is nearing trial after nearly a decade of back-and-forth. US District Judge James Ware ruled for Apple in an initial version of the case, finding there was nothing illegal about installing software that made their product incompatible with competitors. The plaintiffs returned in 2010 with a new complaint, focused on RealNetworks' specific work-around for the Apple DRM and Apple's counter-attack, adding new DRM to thwart the RealNetworks solution. Ware retired in 2012, and the case moved to Gonzales Rogers.

reader comments

180