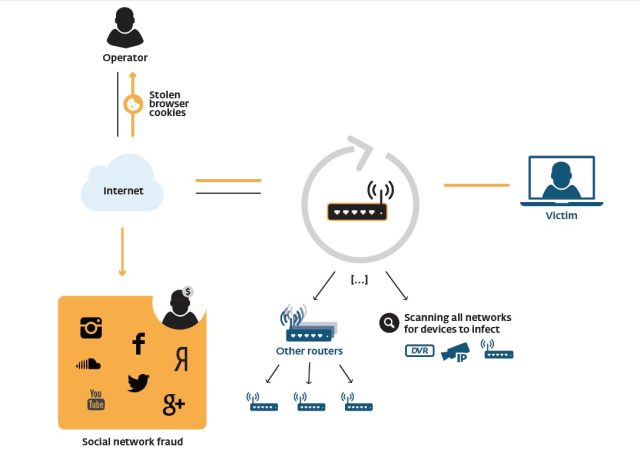

A worm that targets cable and DSL modems, home routers, and other embedded computers is turning those devices into a proxy network for launching armies of fraudulent Instagram, Twitter, and Vine accounts as well as fake accounts on other social networks. The new worm can also hijack routers' DNS service to route requests to a malicious server, steal unencrypted social media cookies such as those used by Instagram, and then use those cookies to add "follows" to fraudulent accounts. This allows the worm to spread itself to embedded systems on the local network that use Linux-based operating systems.

The malware, dubbed "Linux/Moose" by Olivier Bilodeau and Thomas Dupuy of the security firm ESET Canada Research, exploits routers open to connections from the Internet via Telnet by performing brute-force login attempts using default or common administrative credentials. Once connected, the worm installs itself on the targeted device.

Moose spreads itself using a file named elan2—"élan" is the French word for moose, Bilodeau and Dupuy explained in their report. Once installed, the malware begins to watch traffic passing through the router for unencrypted cookies from Web browsers and mobile applications, which may be passed to unencrypted sites that leverage social network features:

- Twitter: twll, twid

- Facebook: c_user

- Instagram: ds_user_id

- Google: SAPISID, APISID

- Google Play / Android: LAY_ACTIVE_ACCOUNT

- Youtube: LOGIN_INFO

The worm begins to scan both other Internet addresses within the same ISP network, other random IP addresses, and local network addresses for other vulnerable devices. Infected devices advertise themselves on port 10073; the worm attempts to connect to this port first before launching Telnet attacks, and it moves on if it gets a successful connection. The malware also attempts to use shell commands on the infected router to change DNS settings, replacing existing domain name servers with malicious ones that could route Web requests by the router's users to lookalike sites—or sites laden with exploit malware.

The main purpose of Moose, however, appears to be to create a network of covert HTTP proxies that can be used by the worm's command and control (C&C) servers to communicate with social networks. While this traffic is encrypted using HTTPS, the researchers were able to trace which sites the traffic was going to and establish a link between the traffic and fraudulent social media accounts. The proxy service is created on TCP port 2318 on the router's Internet network interface, taking incoming Web requests from a whitelisted set of IP addresses and redirecting them as HTTPS requests to social media sites. The most heavily targeted social networks were Instagram (accounting for 47 percent of the traffic analyzed by ESET), then Twitter and Vine (49 percent).

Bilodeau and Dupuy were able to monitor the accounts accessed by an infected router through the proxy service, and they saw "more than 700 Instagram accounts accessed... over about a month." They watched accounts get created through the tunnels and found that they were followed by about 40 accounts within a few hours. The accounts, in turn, were apparently used as paid "follows" for commercial accounts, including a wedding planner in Riyadh and a Brazilian site advertising paid Facebook followers.

While not intended to target Internet of Things devices specifically, Bilodeau and Dupuy found that Moose could infect a number of such devices, including medical ones. "Based on recent security research, we have evidence to state that even medical devices like the Hospira Drug Infusion Pump could be infected with Linux/Moose," the pair wrote. While these infections were essentially just "collateral damage," the worm could have an impact on the safe operation of these devices.

Because of the way that the worm communicates, the ESET researchers were unable to determine the number of devices that have been infected by Moose, which they say they first found late in July of 2014. But based on data obtained from the Internet Storm Center for activity on port 10073 (not a port commonly used by any application on the Internet), they found a rise in traffic that indicates fairly wide distribution of the worm. They have also observed changes made to the malware by C&C servers that allowed the operators of the worm to throttle the amount of scanning done by infected systems—making their operations less noticeable in network traffic.

Fortunately, Linux/Moose apparently has no persistence on a router or other embedded computing device. Once the router is powered off, it restarts without the worm present. But if left poorly configured, routers that are reset could quickly be re-infected by other routers or devices on the local network that have been compromised.

reader comments

46