NoScript, Firebug, and other popular Firefox add-on extensions are opening millions of end users to a new type of attack that can surreptitiously execute malicious code and steal sensitive data, a team of researchers reported.

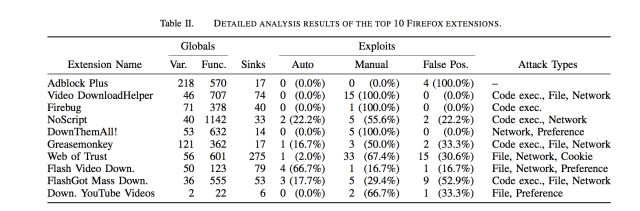

The attack is made possible by a lack of isolation in Firefox among various add-ons installed by an end user. The underlying weakness has been described as an extension reuse vulnerability because it allows an attacker-developed add-on to conceal its malicious behavior by invoking the capabilities of other add-ons. Instead of directly causing a computer to visit a booby-trapped website or download malicious files, the add-on exploits vulnerabilities in popular third-party add-ons that allow the same nefarious actions to be carried out. Nine of the top 10 most popular Firefox add-ons contain exploitable vulnerabilities. By piggybacking off the capabilities of trusted third-party add-ons, the malicious add-on faces much better odds of not being detected.

"These vulnerabilities allow a seemingly innocuous extension to reuse security-critical functionality provided by other legitimate, benign extensions to stealthily launch confused deputy-style attacks," the researchers wrote in a paper that was presented last week at the Black Hat security conference in Singapore. "Malicious extensions that utilize this technique would be significantly more difficult to detect by current static or dynamic analysis techniques, or extension vetting procedures."

Of the top 10 most popular add-ons vetted by Mozilla officials and made available on the Mozilla website, only Adblock Plus was found to contain no flaws that could be exploited by a malicious add-on that relied on reuse vulnerabilities. Besides NoScript, Video DownloadHelper, Firebug, Greasemonkey, and FlashGot Mass Down all contained bugs that made it possible for the malicious add-on to execute malicious code. Many of those apps, and many others analyzed in the study, also made it possible to steal browser cookies, control or access a computer's file system, or to open webpages to sites of an attacker's choosing.

The researchers noted that attackers must clear several hurdles for their malicious add-on to succeed. First, someone must go through the trouble of installing the trojanized extension. Second, the computer that downloads it must have enough vulnerable third-party add-ons installed to achieve the attackers' objective. Still, the abundance of vulnerable add-ons makes the odds favor attackers, at least in many scenarios.

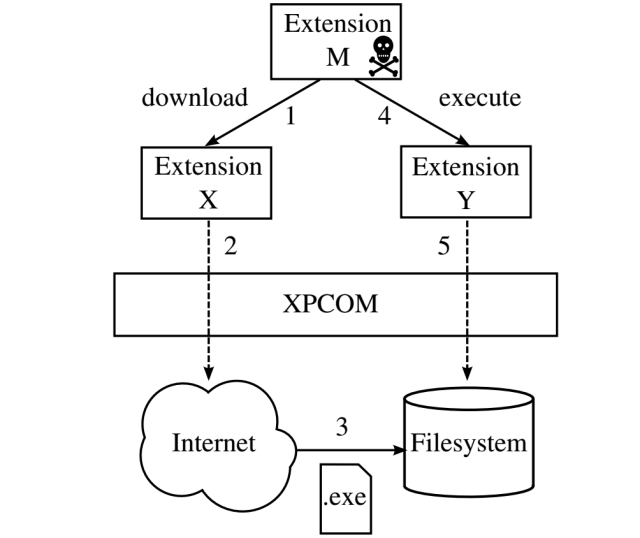

In many cases, a single add-on contains all the functionality an attacker add-on needs to cause a computer to open a malicious website. In other cases, the attacker add-on could exploit one third-party add-on to download a malicious file and exploit a second third-party add-on to execute it. In the event that a targeted computer isn't running any third-party add-ons that can be exploited, the attacker-developed add-on can be programmed to provide what's known as a "soft fail" so that the end user has no way of detected an attempted exploit. Here's a diagram showing how the new class of attack works.

"We note that while it is possible to combine multiple extension-reuse vulnerabilities in this way to craft complex attacks, it is often sufficient to use a single vulnerability to successfully launch damaging attacks, making this attack practical even when a very small number of extensions are installed on a system," the researchers wrote. "For example, an attacker can simply redirect a user that visits a certain URL to a phishing website or automatically load a web page containing a drive-by-download exploit."

Proof of concept

The researchers said they developed an add-on containing about 50 lines of code that passed both Mozilla's automated analysis and its full review process. Ostensibly, ValidateThisWebsite—as the add-on was called—analyzed the HTML code of a given website to determine if it was compliant with current standards. Behind the scenes, the add-on made a cross-extension call to NoScript that caused Firefox to open a Web address of the researchers' choosing.

The vulnerability is the result of a lack of add-on isolation in the Firefox extension architecture. By design, Firefox allows all JavaScript extensions installed on a system to share the same JavaScript namespace, which is a digital container of specific identifiers, functions, methods, and other programming features used in a particular set of code. The shared namespace makes it possible for extensions to read from and write to global variables defined by other add-ons, to call or override other global functions, and to modify instantiated objects. The researchers said that a newer form of Firefox extension built on the alternative JetPack foundation theoretically provides the isolation needed to prevent cross-extension calls. In practice, however, JetPack extensions often contain enough non-isolated legacy code to make them vulnerable.

In an e-mail, Firefox's vice president of product issued the following statement:

The way add-ons are implemented in Firefox today allows for the scenario hypothesized and presented at Black Hat Asia. The method described relies on a popular add-on that is vulnerable to be installed, and then for the add-on that takes advantage of that vulnerability to also be installed.

Because risks such as this one exist, we are evolving both our core product and our extensions platform to build in greater security. The new set of browser extension APIs that make up WebExtensions, which are available in Firefox today, are inherently more secure than traditional add-ons, and are not vulnerable to the particular attack outlined in the presentation at Black Hat Asia. As part of our electrolysis initiative—our project to introduce multi-process architecture to Firefox later this year—we will start to sandbox Firefox extensions so that they cannot share code.

In the meantime, the researchers said Firefox users would benefit from improvements made to the screening process designed to detect malicious add-ons when they're submitted. To that end, they have developed an application they called CrossFire that automates the process of finding cross-extension vulnerabilities. In their paper, they proposed that it or a similar app be incorporated into the screening process.

"Naturally, we do not intend our work to be interpreted as an attack on the efforts of Firefox's cadre of extension vetters, who have an important and difficult job," the researchers wrote. "However, since the vetting process is the fundamental defense against malicious extensions in the Firefox ecosystem, we believe it is imperative that (i) extension vetters be made aware of the dangers posed by extension-reuse vulnerabilities, and that (ii) tool support be made available to vetters to supplement the manual analyses and testing they perform."

Listing image by Andrew Cunningham

reader comments

92