What looked like a solid defense win for Samsung in the second Apple v. Samsung litigation has suddenly slipped away, due to an opinion issued earlier today by the full US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

The second Apple v. Samsung trial led to a $120 million jury verdict in Apple's favor. Samsung appealed, and, in February, a three-judge appeals panel said that the jury got it wrong. The judges stripped away Apple's win, saying one patent wasn't infringed and the other two were invalid.

Apple got the full court to take up the case, and the three judges who sided with Samsung didn't win a single ally. An opinion (PDF) issued earlier today restores Apple's win entirely on an 8-3 vote. (One of the 12 sitting Federal Circuit judges, Richard Taranto, did not participate.)

The earlier opinion held that US Patent No. 5,946,647, which describes how to turn phone numbers and other software "structures" into links, wasn't infringed because Samsung products didn't use an "analyzer server" as the term was defined. The opinion also found that US Patent Nos. 8,046,721 and 8,074,172, which respectively cover Apple's slide-to-unlock and autocorrect features, were invalid in light of prior art.

Today's opinion by the full court, written by Circuit Judge Kimberly Moore, wholly rejects those earlier findings, saying the three-judge panel went too far in reversing "nearly a dozen jury fact findings" involving infringement, prior art, copying, and other matters. Only the three judges from the original panel dissented, holding fast in their view that Samsung should win the day.On the '647 patent, the eight-judge majority held that "substantial evidence" supported the jury's decision that the accused devices used an "analyzer server." The dispute was over where the shared library code performs its functions—Apple argued that Samsung's shared library code is "separate" from the client, while Samsung argued there was no separate server. "The concept that the analyzer server must be 'standalone' or 'run on its own'... has no foundation in the '647 patent, in our prior Motorola decision, or in the parties briefs on appeal to this court," Judge Moore's majority opinion states.

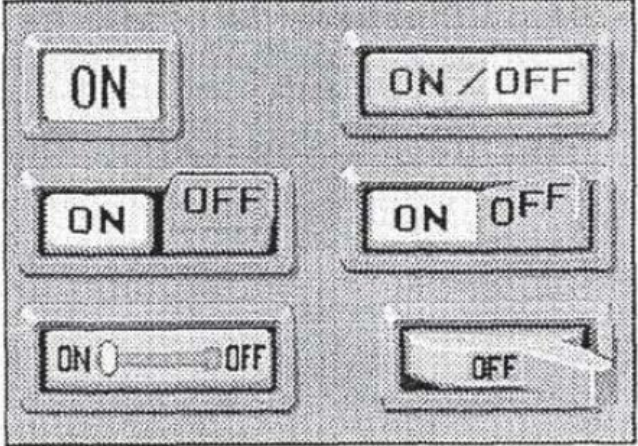

On the '721 slide-to-unlock patent, the majority noted that the patent emphasized making phone activation "user-friendly" and "efficient" while still preventing pocket dialing. Apple didn't contest that two prior art references disclosed all the elements of their patent claim, but argued that a person would not have been "motivated to combine" the various references. (One of the references, the Plaisant patent, is pictured above.)

"[A] skilled artisan designing a mobile phone would not have been motivated to turn to a wall-mounted air conditioning controller to solve a pocket dialing problem," argued Apple, and the appeals court agreed. "[S]ubstantial evidence supports the jury's fact findings that Samsung failed to establish a motivation to combine," writes Moore.

The opinion also cites Apple executive Philip Schiller's testimony at trial, touting how important the slide-to-unlock feature was in Apple's advertising. "That one gesture... you get an instant idea of how multitouch works so that you're doing a gesture on the screen, and it does something simple and useful to you, and that it's easy to use," Schiller said during his 2014 testimony.

"Finally, the video of the crowd 'burst[ing] into cheers' when Steve Jobs demonstrated the slide to unlock feature supports a conclusion that consumers valued this particular feature," wrote Moore.

As to the '172 autocorrect patent, the earlier panel agreed with Samsung that the Apple patent wasn't a serious improvement over two previous methods, including the US Patent No. 7,880,730, entitled "keyboard system with automatic correction."

AApple’s expert testified that the earlier system didn’t display text while the user typed, so it doesn’t have all the features disclosed by Apple’s patent. The same expert argued that another piece of prior art, by Xrgomics, involves "word completion" that offers alternative words, and is not directed toward spelling correction. A reasonable jury could have agreed with Apple on those points, Moore wrote in her opinion today.

All three judges from the original panel filed sharply worded dissenting opinions, disagreeing not just on the merits of the patents but about the manner in which the case was heard. Circuit Judge Jimmie Reyna, for instance, complained that the full court chose to overturn the case on narrow grounds and did so without additional briefing from the parties, amici, or the government—all standard practice in a full-court "en banc" case.

"The en banc decision neither resolves a disagreement among the court's decisions nor answers any exceptionally important question," wrote Reyna in his dissent. "The court should not have granted en banc review in this case."

Today's decision involved the second Apple v. Samsung litigation. The first Apple v. Samsung case, which resulted in Samsung making a payment of $548 million to Apple after losing a jury verdict, will go to the US Supreme Court next week. It will be the first design patent case heard by the high court in a century.

reader comments

138