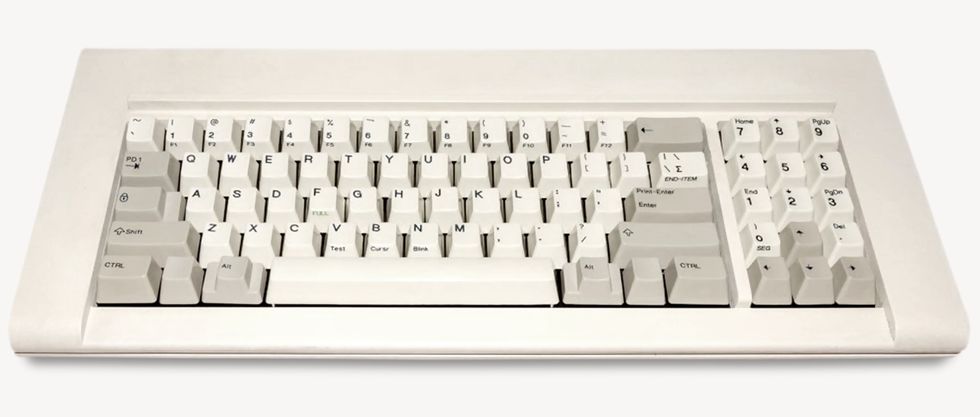

You may not know the Model F by name, but you know it by sound—the musical thwacking of flippers slapping away. The sound of the '80s office. The IBM Model F greeted the world in 1981 with a good ten pounds of die-cast zinc and keys that crash down on buckling metal springs as they descend. It's a sensation today's clickiest keyboards chase, but will never catch. And now it's coming back.

The second coming of the high-quality Model F (not to be confused with its more affordable plastic successor, the Model M) isn't a throwback attention grab from IBM, nor a nostalgia play from Big Keyboard. Instead, it's the longtime work of a historian in love with the retro keyboard's unparalleled sound and feel, but frustrated by the limitations of actual decades-old tech.

The Model F Keyboards project, now taking preorders for the new line of authentic retro-boards, was started by Joe Strandberg, a Cornell University grad who's taken up keyboard wizardry as a nights-and-weekends hobby. He started as a collector and restorer of genuine Model F keyboards—originally produced from 1981 to 1994—a process that familiarized him with their virtues and their flaws.

"The first family computer we had was an IBM PC," Strandberg told me. "And, I know from this from watching old home movies: The first keyboard I typed on was a Model F." It's a simple story, and one that's familiar to plenty of nerds of a certain age (including me). But it's not rose-colored glasses that make you remember that 1980s keyboard fondly. It really was the best.

All keyboards work by the same basic principle. When you press a key, you engage a mechanism that completes a circuit, telling the computer to put a character on the screen. Most modern day keyboards, like those you find on a laptop, are "membrane" keyboards. These keys are thin plastic slabs suspended over rubbery domes that squish when you depress them, completing the circuit. They can be made well, but have very short throw (the distance the keys travel down before they bottom out) and virtually no click. You'll be hard-pressed to find any keyboard nerd that's particularly fond of them.

Modern-day mechanical keyboards are different. Instead of rubber domes, they tend to use individual switches with innards made of plastic and metal. Cherry is the brand name to know in this world, offering switches of varying design to provide different feelings—stiffer sprints for firmer pushback, and, of course, keys designed to clack. The modern-day standard for "clickiness" are Cherry's Blue switches. Each one contains two plastic parts that smack against each other on the way down, offering a signature click.

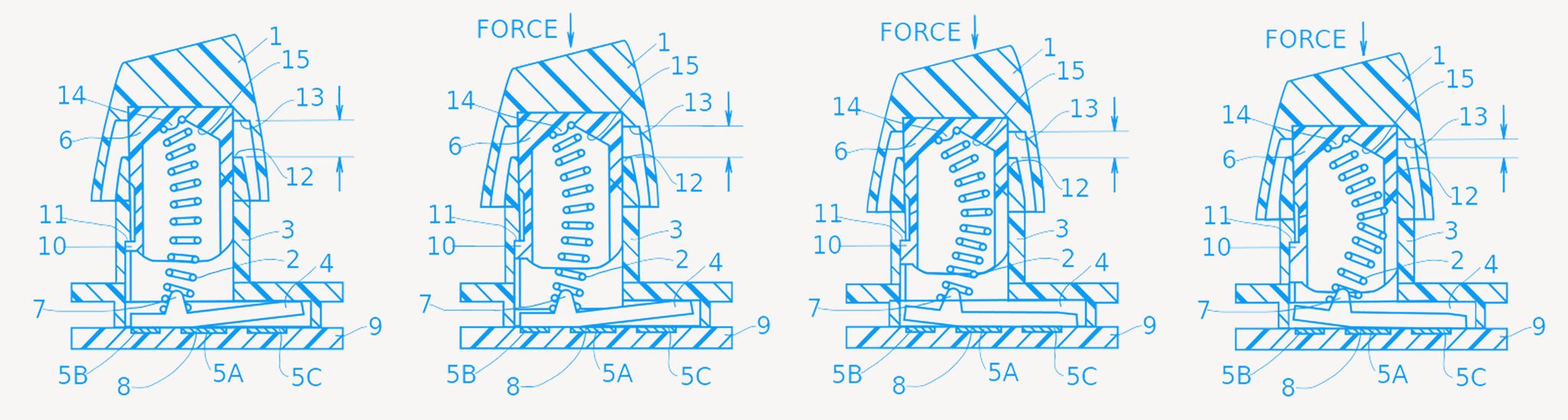

But both of these mechanical solutions are a shadow of their predecessor, IBM's buckling spring. As detailed in the now-expired 1978 patent, these keyboards use a spring that buckles (go figure) as the key atop it is depressed. This buckling motion then torques a small plastic paddle beneath it, and the paddle slaps into the printed circuit board (PCB) and metal plate underneath. It's that thwacking that both completes the circuit and gives a buckling spring keyboard its irreproducible sound.

It's a sound and sensation Strandberg has spent years dissecting, and it shows in his lyrical description: "You've got huge pieces of steel, the flippers slapping and resonating between two metal sandwich layers. It's a musical kind of interaction."

It's wildly difficult to reproduce. Some keyboard enthusiasts have endeavored to squeeze the buckling spring mechanism into a modern form, but to lukewarm results. They face engineering challenges but also rightful skepticism as to whether it's even possible. Strandberg is certainly wary of such an approach. "There really is no buckling spring self-contained switch," he says. "A self-contained switch would lose the richness from the steel plates."

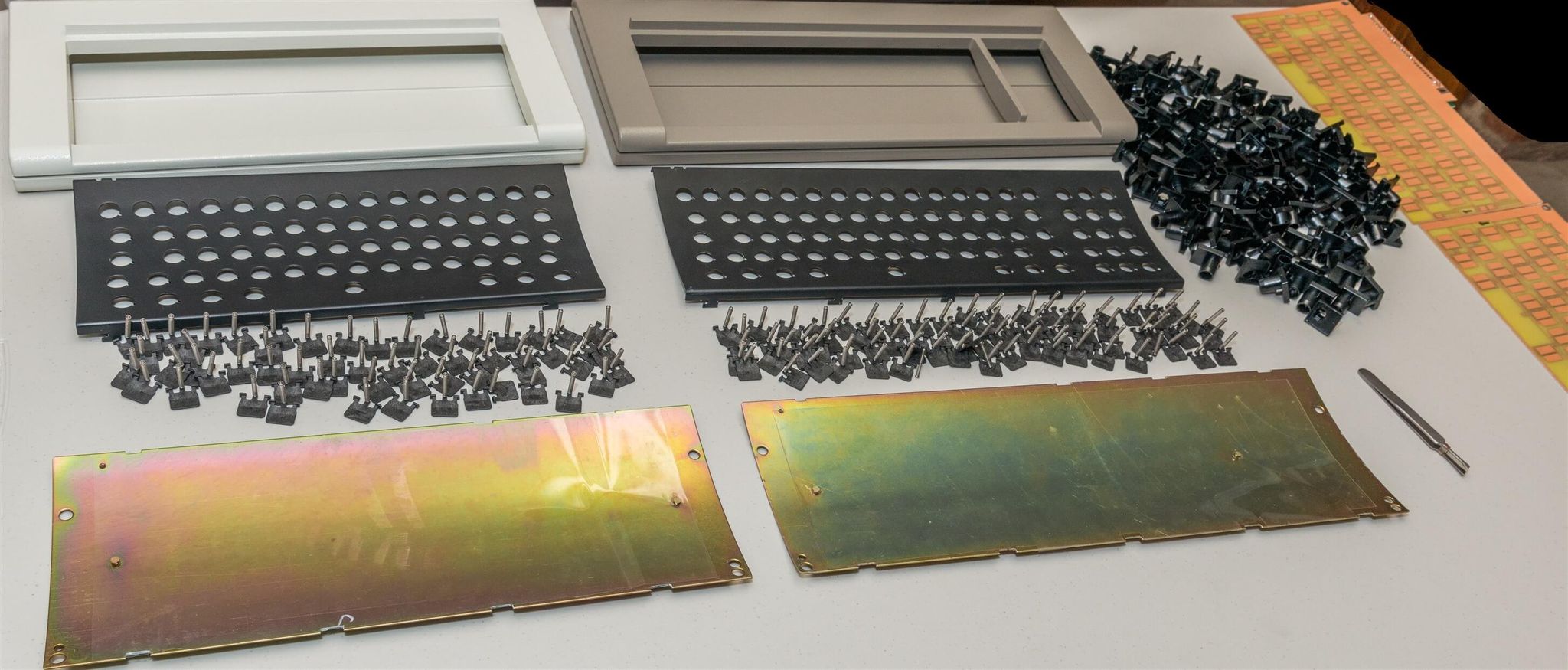

Strandberg takes a more holistic tack: build the physical form of an old Model F Keyboard in its entirety, exactly like they used to be made in the 1980s, or at least as close to that standard as possible. Working with a factory in China, Strandberg has carefully overseen the reproduction process one step at time, from the springs to the unique powder-coating on the keyboard's zinc case. Despite the expense (Strandberg estimates spending $100,000 to revive the tooling necessary for the production run), it was the only viable option given the kind of abuse your average keyboard takes on a daily basis. "With 3D printing," he says, "the keyboard wouldn't last a year."

But manufacturing is a painstaking process that has lead to continuing delays. In fact, the most recent preorder deadline just slipped from the end of June to the end of July. "I was initially expecting to get these shipped out at the end of last year and we're probably looking at the end of this year," Strandberg says. "They had to figure out how to do the powder coating to make it look like the old, bumpy, splotchy, IBM powder coating on the cases. That took them about two or three extra months. And the standards that IBM had for the keys were so precise that it's taken them a few extra months to get the key molds precise."

That attention to detail matters because quality is a Model F calling card. The first keyboard of its type to be released by IBM, the Model F made no compromises. It weighed nearly 10 pounds thanks to its metal case and cost a whopping $600 when debuted, which translates to some $1,700 today, the cost of a top-of-the-line gaming rig. It's a number that will, maybe, help nerds (and their frustrated spouses) swallow the new Model F's more modest $300 price point, which reaches up towards $400, depending on various optional embellishments.

It's a cost plenty of people are willing to pay. Strandberg's got preorders for more than 500 new keyboards, totaling a quarter of a million dollars in sales, all that with little more to show for his work so far than some videos of prototypes. The first prototypes off the assembly line only just made their way underneath the fingers of enthusiasts at a recent keyboard meet-up, to good initial reviews.

For anyone who longs to have the buckling spring back again, the options are limited. Authentic Model F keyboards go for hundreds of dollars online and require extensive modification before they'll work with modern computer. Its successor, the Model M, is more readily available and easier to attach to today's PCs and Macs, but has a cheaper plastic body.

Even thrift-store adventurers who find a functioning antique will be hamstrung by the ancient firmware that powers these old-school boards, firmware that doesn't support modern features like programmability or the option to reassign keys. In fact, this arcane firmware was the bane of retrocomputing enthusiasts until just recently, when one endeavoring hacker managed to reverse-engineer the decades-old code by digging through IBM patents and released a modernized version as an open-source project. It was an act that effectively unshackled buckling spring technology from some 35 years of cyber-bondage. "It was the main thing that made the project finally feasible," Strandberg says.

This new breed of Model Fs will be limited in number, though the deadline for ponying up for keeps slipping back due to the manufacturing delays. New Model Fs will be made, yes. But not in perpetuity. "Every run has enormous overhead," Strandberg says. "Even if you have the molds already, you're still paying the factory to configure all their machinery to make your parts." Fortunately, Strandberg is planning on two runs. One for early birds, who are content to hop on board even with test units sight unseen, and a second run a year or two down the line for people who are perhaps a little more skeptical or skittish about the price.

To Strandberg, and the kind of people who would shell out a few hundred dollars for a limited edition keyboard, the case for the splurge is clear. "If you're a writer, a programmer, someone who works in front of computer, you're going to be there a good part of your day so why not type on the best? This is something that IBM spent millions of dollars developing, getting the perfect layout, getting the perfect shape and technology." The original Model Fs have lasted for decades and many of them are still kicking, and Strandberg hopes his new ones—built meticulously in their image and with eyes set on the future—will last for at least that long, and beyond.

You can pre-order your own Model F until July 31st. Just remember to save a few bucks to buy some earplugs for your coworkers.