The Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation (IFTF) is a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and improvement of technologies enabling the digital art form we call interactive fiction. When a Community Moderator for Opensource.com suggested an article about IFTF, the technologies and services it supports, and how it all intersects with open source, I found it a novel angle to the decades-long story I’ve so often told. The history of IF is longer than—but quite enmeshed with—the modern FOSS movement. I hope you’ll enjoy my sharing it here.

Definitions and history

To me, the term interactive fiction includes any video game or digital artwork whose audience interacts with it primarily through text. The term originated in the 1980s when parser-driven text adventure games—epitomized in the United States by Zork, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and the rest of Infocom’s canon—defined home-computer entertainment. Its mainstream commercial viability had guttered by the 1990s, but online hobbyist communities carried on the tradition, releasing both games and game-creation tools.

After a quarter century, interactive fiction now comprises a broad and sparkling variety of work, from puzzle-laden text adventures to sprawling and introspective hypertexts. Regular online competitions and festivals provide a great place to peruse and play new work: The English-language IF world enjoys annual events including Spring Thing and IFComp, the latter a centerpiece of modern IF since 1995—which also makes it the longest-lived continually running game showcase event of its kind in any genre. IFComp’s crop of judged-and-ranked entries from 2017 shows the amazing diversity in form, style, and subject matter that text-based games boast today.

(I specify "English-language" above because IF communities tend to self-segregate by language, perhaps due to the technology's focus on writing. There are also annual IF events in French and Italian, for example, and I've heard of at least one Chinese IF festival. Happily, these borders are porous; during the four years I managed IFComp, it has welcomed English-translated work from all international communities.)

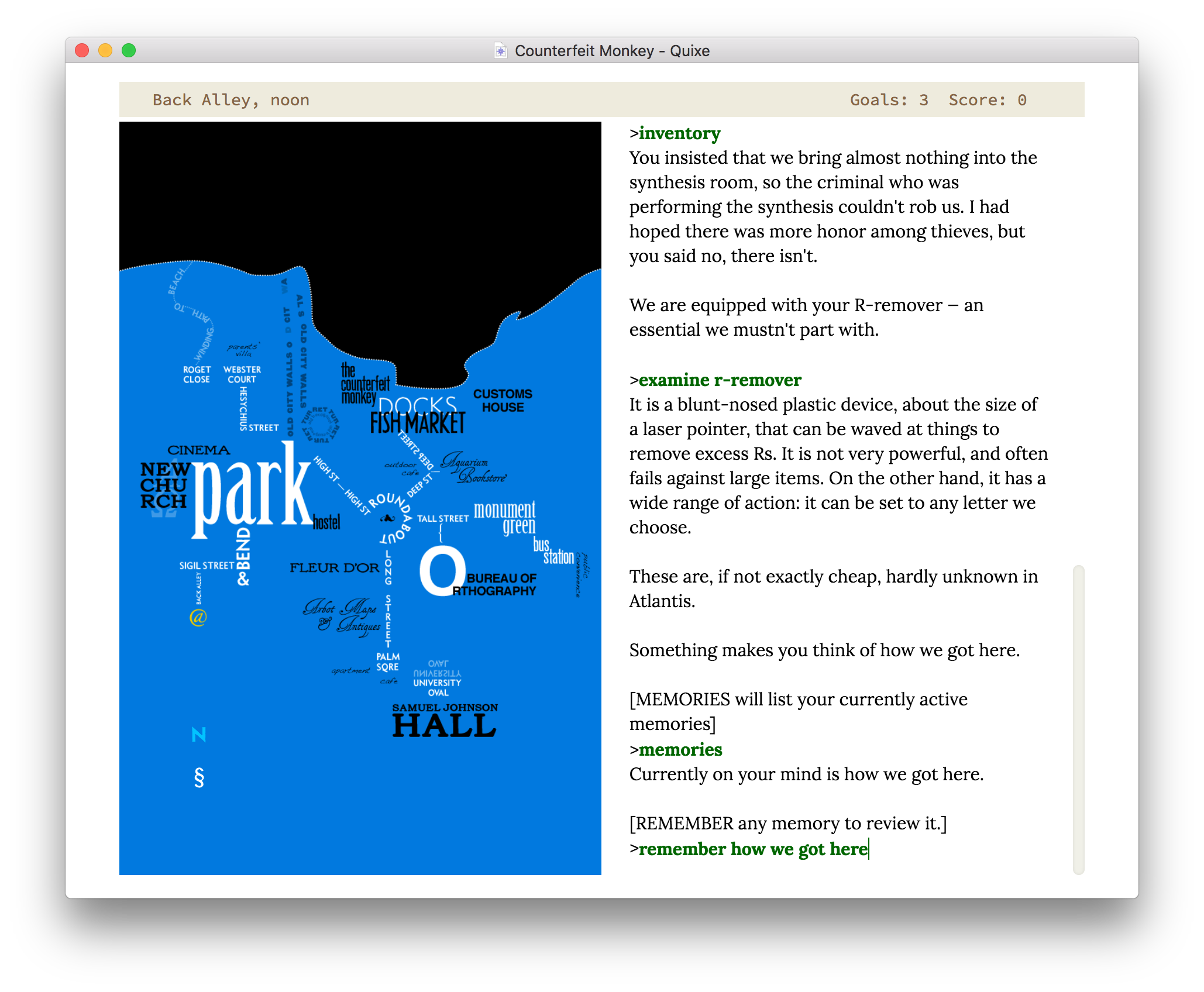

Starting a new game of Emily Short's "Counterfeit Monkey," running on the interpreter Lectrote (both open source software).

Also due to its focus on text, IF presents some of the most accessible platforms for both play and authorship. Almost anyone who can read digital text—including users of assistive technology such as text-to-speech software—can play most IF works. Likewise, IF creation is open to all writers willing to learn and work with its tools and techniques.

This brings us to IF’s long relationship with open source, which has helped enable the art form’s availability since its commercial heyday. I'll provide an overview of contemporary open-source IF creation tools, and then discuss the ancient and sometimes curious tradition of IF works that share their source code.

The world of open source IF tools

A number of development platforms, most of which are open source, are available to create traditional parser-driven IF in which the user types commands—for example, go north, get lamp, pet the cat, or ask Zoe about quantum mechanics—to interact with the game’s world. The early 1990s saw the emergence of several hacker-friendly parser-game development kits; those still in use today include TADS, Alan, and Quest—all open, with the latter two bearing FOSS licenses.

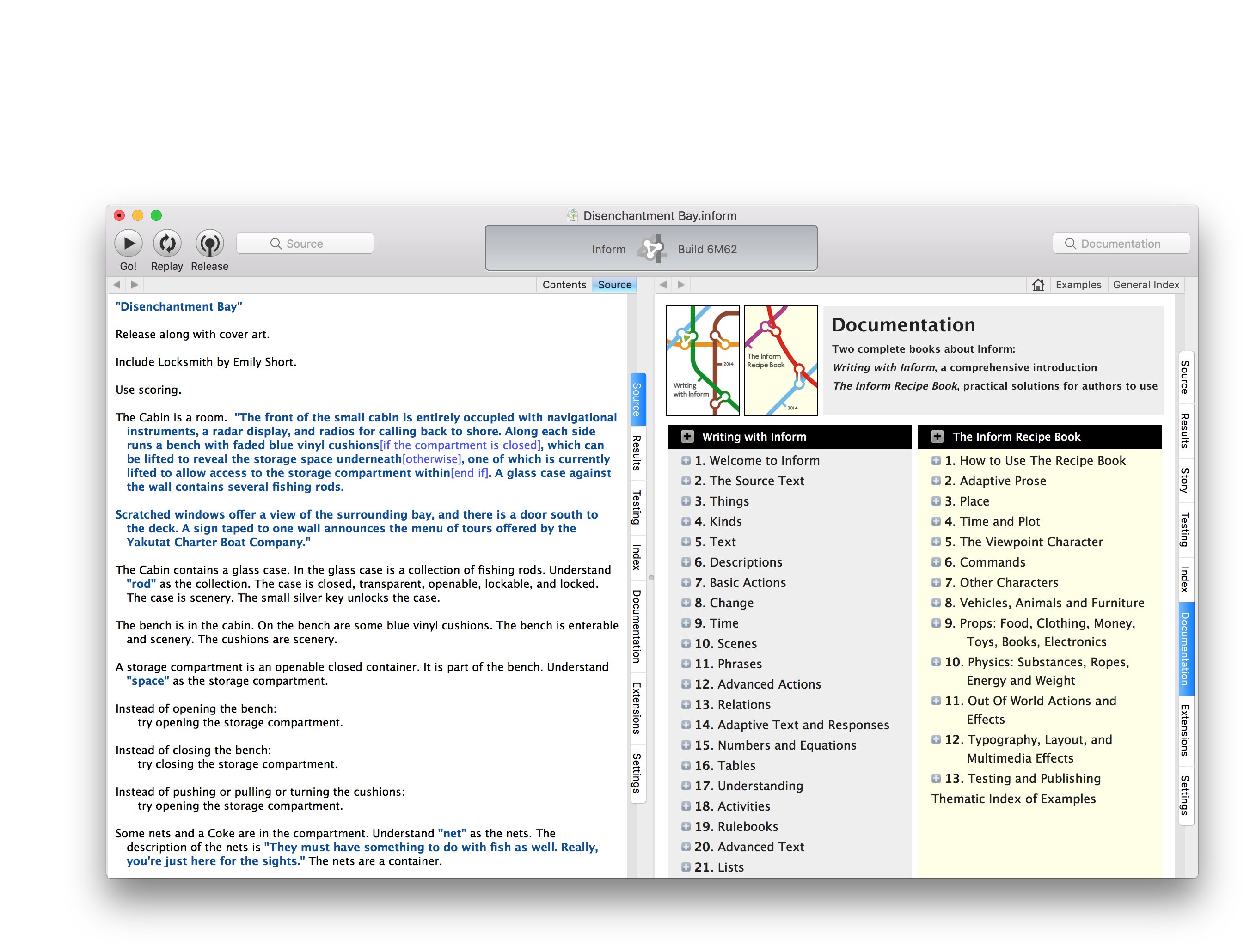

But by far the most prominent of these is Inform, first released by Graham Nelson in 1993 and now maintained by a team Nelson still leads. Inform source is semi-open, in an unusual fashion: Inform 6, the previous major version, makes its source available through the Artistic License. This has more immediate relevance than may be obvious, since the otherwise proprietary Inform 7 holds Inform 6 at its core, translating its remarkable natural-language syntax into its predecessor’s more C-like code before letting it compile the work down into machine code.

The Inform 7 IDE, loaded up with documentation and a sample project.

Inform games run on a virtual machine, a relic of the Infocom era when that publisher targeted a VM so that it could write a single game that would run on Apple II, Commodore 64, Atari 800, and other flavors of the "home computer." Fewer popular operating systems exist today, but Inform’s virtual machines—the relatively modern Glulx or the charmingly antique Z-machine, a reverse-engineered clone of Infocom’s historical VM—let Inform-created work run on any computer with an Inform interpreter. Currently, popular cross-platform interpreters include desktop programs like Lectrote and Gargoyle or browser-based ones like Quixe and Parchment. All are open source.

If the pace of Inform’s development has slowed in its maturity, it remains vital through an active and transparent ecosystem—just like any other popular open source project. In Inform’s case, this includes the aforementioned interpreters, a collection of language extensions (usually written in a mix of Inform 6 and 7), and of course, all the work created with it and shared with the world, sometimes with source included (I’ll return to that topic later in this article).

IF creation tools invented in the 21st century tend to explore player interactions outside of the traditional parser, generating hypertext-driven work that any modern web browser can load. Chief among these is Twine, originally developed by Chris Klimas in 2009 and under active development by many contributors today as a GNU-licensed open source project. (In fact, Twine can trace its OSS lineage back to TiddlyWiki, the project from which Klimas initially derived it.)

Twine represents a sort of maximally open and accessible approach to IF development: Beyond its own FOSS nature, it renders its output as self-contained websites, relying not on machine code requiring further specialized interpretation but the open and well-exercised standards of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. As a creative tool, Twine can match its own exposed complexity to the creator’s skill level. Users with little or no programming knowledge can create simple but playable IF work, while those with more coding and design skills—including those developing these skills by making Twine games—can develop more sophisticated projects. Little wonder that Twine’s visibility and popularity in educational contexts has grown quite a bit in recent years.

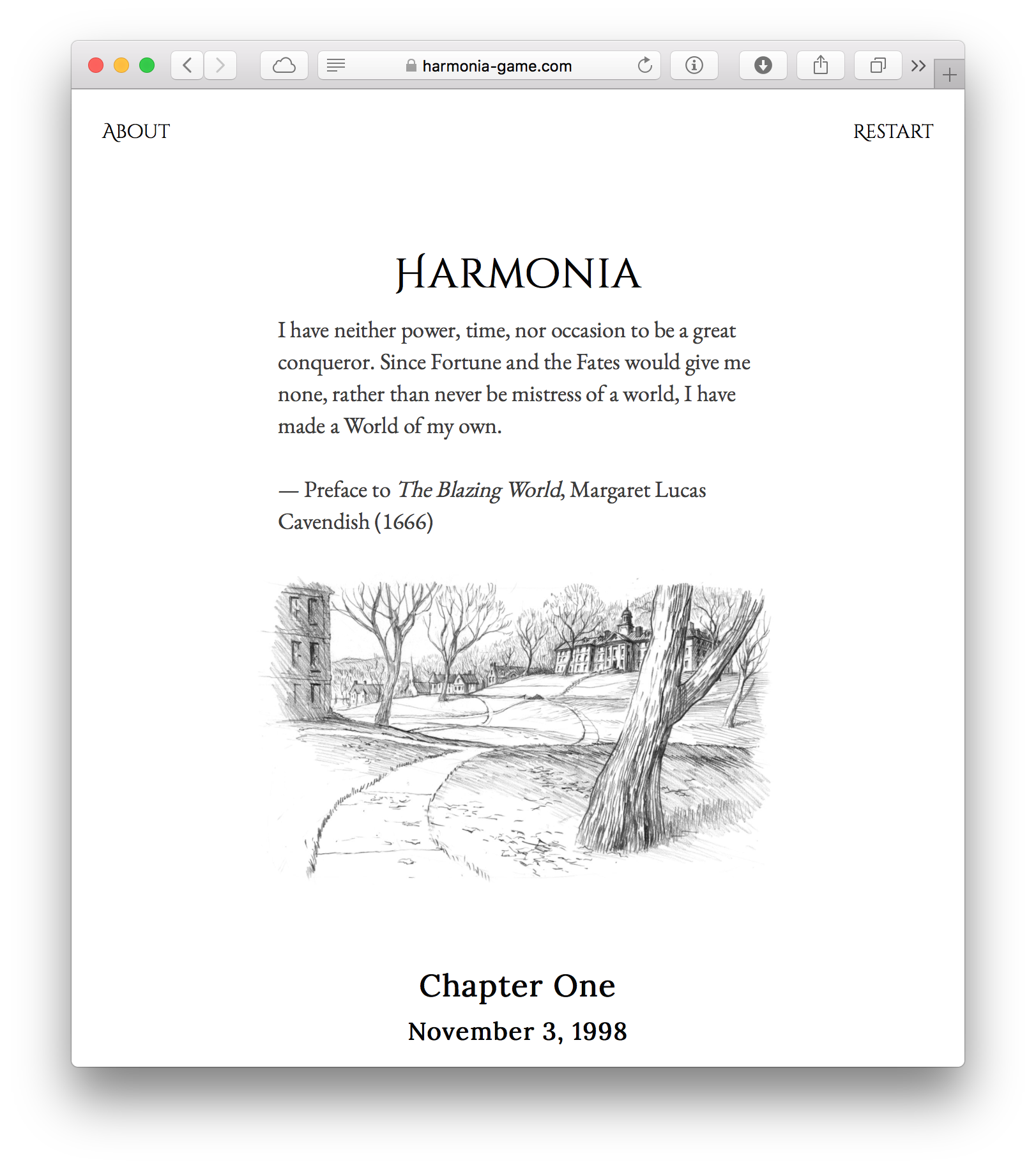

Other noteworthy open source IF development projects include the MIT-licensed Undum by Ian Millington, and ChoiceScript by Dan Fabulich and the Choice of Games team—both of which also target the web browser as the gameplay platform. Looking beyond strict development systems like these, web-based IF gives us a rich and ever-churning ecosystem of open source work, such as furkle’s collection of Twine-extending tools and Liza Daly’s Windrift, a JavaScript framework purpose-built for her own IF games.

Programs, games, and game-programs

Twine benefits from a standing IFTF program dedicated to its support, allowing the public to help fund its maintenance and development. IFTF also directly supports two long-time public services, IFComp and the IF Archive, both of which depend upon and contribute back into open software and technologies.

The opening of Liza Daly's "Harmonia," created with the Windrift open source IF-creation framework.

The Perl- and JavaScript-based application that runs the IFComp’s website has been a shared-source project since 2014, and it reflects the stew of FOSS licenses used by its IF-specific sub-components, including the various code libraries that allow parser-driven competition entries to run in a web browser. The IF Archive—online since 1992 and an IFTF project since 2017—is a set of mirrored repositories based entirely on ancient and stable internet standards, with a little open source Python script to handle indexing.

At last, the fun part: Let's talk about open source text games

The bulk of the archive comprises games, of course—years and years of games, reflecting decades of evolving game-design trends and IF tool development.

Lots of IF work shares its source code, and the community’s quick-start solution for finding it is simple: Search the IFDB for the tag "source available". (The IFDB is yet another long-running IF community service, run privately by TADS creator Mike Roberts.) Users who are comfortable with a more bare-bones interface may also wish to browse the /games/source directory of the IF Archive, which groups content by development platform and written language (there's also a lot of work either too miscellaneous or too ancient to categorize floating at the top).

A little bit of random sampling of these code-sharing games reveals an interesting dilemma: Unlike the wider world of open source software, the IF community lacks a generally agreed-upon way of licensing all the code that it generates. Unlike a software tool—including all the tools we use to build IF—an interactive fiction game is a work of art in the most literal sense, meaning that an open source license intended for software would fit it no better than it would any other work of prose or poetry. But then again, an IF game is also a piece of software, and it exhibits source-code patterns and techniques that its creator may legitimately wish to share with the world. What is an open source-aware IF creator to do?

Some games address this by passing their code into the public domain, either through explicit license or—as in the case of the original 42-year-old Adventure by Crowther and Woods—through community fiat. Some try to split the difference, rolling their own license that allows for free re-use of a game’s exposed business logic but prohibits the creation of work derived specifically from its prose. This is the tack I took when I opened up the source of my own game, The Warbler’s Nest. Lord knows how well that’d stand up in court, but I didn’t have any better ideas at the time.

Naturally, you can find work that simply puts everything under a single common license and never mind the naysayers. A prominent example is Emily Short’s epic Counterfeit Monkey, released in its entirety under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. CC frowns at its application to code, but you could argue that the strangely prose-like nature of Inform 7 source makes it at least a little more compatible with a CC license than a more traditional software project would be.

What now, adventurer?

If you are eager to start exploring the world of interactive fiction, here are a few links to check out:

-

As mentioned above, IFDB and the IF Archive both present browsable interfaces to more than 40 years worth of collected interactive fiction work. Much of this is playable in a web browser, but some require additional interpreter programs. IFDB can help you find and install these.

IFComp’s annual results pages provide another view into the best of this free and archive-available work.

-

The Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation is a charitable non-profit organization that helps support Twine, IFComp, and the IF Archive, as well as improve the accessibility of IF, explore IF’s use in education, and more. Join its mailing list to receive IFTF’s monthly newsletter, peruse its blog, and browse some thematic merchandise.

-

John Paul Wohlscheid wrote this article about open-source IF tools earlier this year. It covers some platforms not mentioned here, so if you’re still hungry for more, have a look.

1 Comment