On Linux, I often use the GNU Emacs editor to write the source code for new programs. I learned GNU Emacs long ago when I was an undergraduate student, and I still have the "finger memory" for all the keyboard shortcuts.

When I started work on FreeDOS in 1994, I wanted to include an Emacs-like text editor. You can find many editors similar to Emacs, such as MicroEmacs, but these all take some shortcuts to fit into the 16-bit address space on DOS. However, I was very pleased to find Freemacs, by Russell "Russ" Nelson.

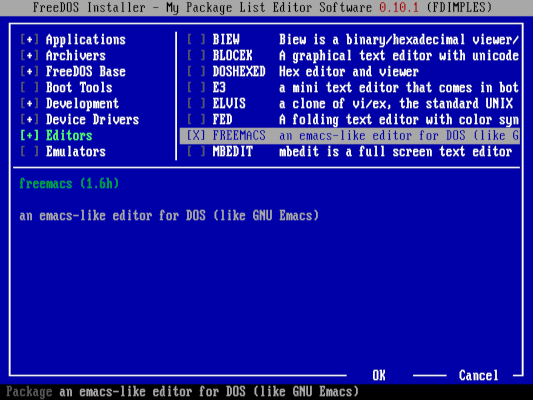

You can find Freemacs in FreeDOS 1.3 RC4, on the Bonus CD. You can use FDIMPLES to install the package, which will install to \APPS\EMACS.

Installing Freemacs from the FreeDOS 1.3 RC4 Bonus CD

(Jim Hall, CC-BY SA 4.0)

Initial setup

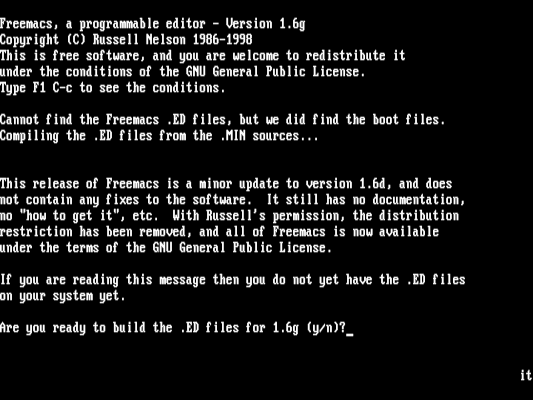

The first time you run Freemacs, the editor will need to "compile" all of the setup files into a form that Freemacs can quickly process. This will take a few minutes to run, depending on your system's speed and memory, but fortunately, you only need to do it once.

Press Y to build the Freemacs MINT files

(Jim Hall, CC-BY SA 4.0)

Freemacs actually processes the editor files in two passes. When Freemacs has successfully completed the first pass, it prompts you to restart the editor so it can finish processing. So don't be surprised that the process seems to start up again—it's just "part 2" of the compilation process.

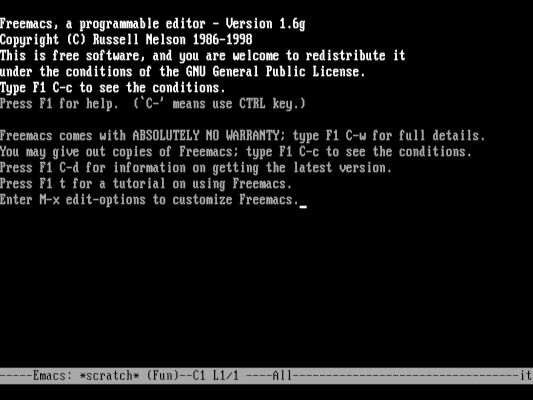

Using Freemacs

To edit a file with Freemacs, start the program with the text file as an argument on the command line. For example, emacs readme.doc will open the Readme file for editing in Freemacs. Typing emacs at the command line, without any options, will open an empty "scratch" buffer in Freemacs.

Starting Freemacs without any files opens a "scratch" buffer

(Jim Hall, CC-BY SA 4.0)

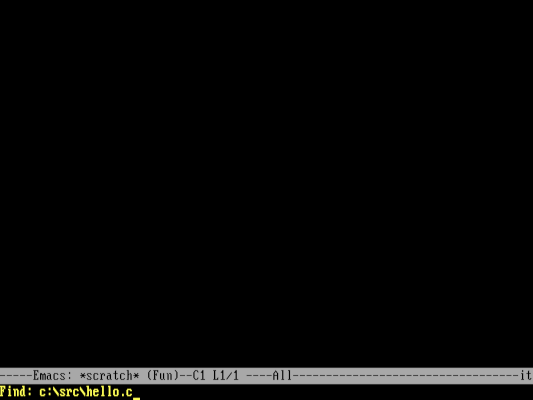

Or, you can start Freemacs without any command-line options, and use the Emacs shortcuts C-x C-f (or M-x find-file). Freemacs then prompts you for a new file to load into the editor. The shortcut prefix C- means you should press the Ctrl key and some other key, so C-x is Ctrl and the x key together. And M-x is shorthand for "press the 'Meta' key (usually Esc) then hit x."

Opening a new file with C-x C-f

(Jim Hall, CC-BY SA 4.0)

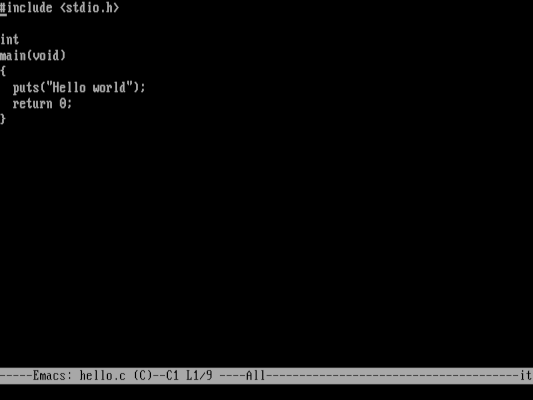

Freemacs automatically detects the file type and attempts to load the correct support. For example, opening a C source file will also set Freemacs to "C-mode."

Editing a C source file in Freemacs

(Jim Hall, CC-BY SA 4.0)

If you also use GNU Emacs (like me), then you are probably curious to get Freemacs to match the C indentation that GNU Emacs uses (2 spaces.) Here is how to set Freemacs to use 2 spaces in C-mode:

- Open a C source file in Freemacs.

- Enter M-x

edit-optionsto edit Freemacs settings. - Use the settings to change both "C-brace-offset" and "C-indent-level" to 2.

- Save and exit Freemacs; you'll be prompted to save settings.

A few limitations

Much of the rest of Freemacs operates like GNU Emacs. If you're already familiar with GNU Emacs, you should feel right at home in Freemacs. However, Freemacs does have a few limitations that you might need to know:

The extension language is not LISP. The biggest difference between GNU Emacs on Linux and Freemacs on FreeDOS is that Freemacs uses a different extension language. Where GNU Emacs implements a LISP-like interpreter, Freemacs implements a different extension language called MINT—based on the string processing language, TRAC. The name "MINT" is an acronym, meaning "MINT Is Not TRAC."

You shouldn't expect to evaluate LISP code in Freemacs. The MINT language is completely different from LISP. For more information on MINT, see the reference manual. We provide the full documentation via the FreeDOS files archive on Ibiblio, at /freedos/files/edit/emacs/docs. In particular, the MINT language is defined in mint.txt and mint2.txt.

Freemacs cannot open files larger than 64 kilobytes. This is a common limitation in many programs. 64kb is the maximum size of the data space for programs that do not leverage extended memory.

There is no "Undo" feature. Be careful in editing. If you make a mistake, you will have to re-edit your file to get it back to the old version. Also, save early and often. For very large mistakes, your best path might be to abandon the version you're editing in Freemacs, and load the last saved version.

The rest is up to you! You can find more information about Freemacs on Ibiblio, at /freedos/files/edit/emacs/docs. For a quick-start guide to Freemacs, read quickie.txt. The full manual is in tutorial.txt.

1 Comment