Open Source and William James

Matt Asay just posted an excellent note connecting Open source and William James. James noted: "True ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate and verify. False ideas are those that we can not. That is the practical difference it makes to us to have true ideas." Matt argues that that is why he likes open source -- because it works. I can't agree more.

I remember saying something very similar in the early days after the open source summit, when we were all first introducing people to this new term. I distinguished between free software, which is a kind of religious movement based on ethical principles, and open source as a pragmatic movement. Open source is like gravity, I said. It's not something that you believe in. It's something that you explore and discover, as with any other science. It's a study of what works.

Matt makes this same argument, except contrasting open source and proprietary software. He says:

Why do I believe open source is the best way to develop, distribute, and support software? Because it works. Some may answer, "But look at Microsoft, Oracle, SAP, etc. Surely they "work" in the sense that they have been massively successful." To this I concur, but with a caveat. Or, rather, with a statement: "at a given moment in time."

That is, the end-to-end proprietary model makes sense, but only in the early phases of a market's growth.

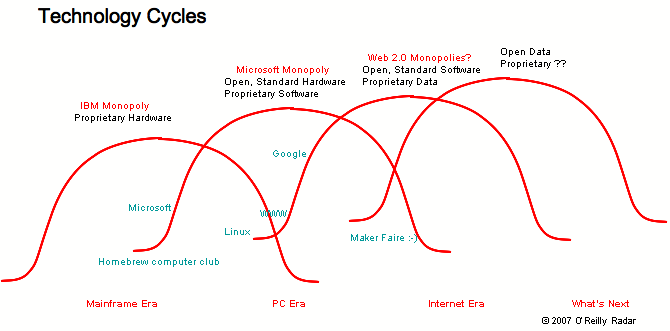

Here I have to part ways with Matt. Both open source AND proprietary software work at a given moment in time. What I've observed (and wrote about in The Open Source Paradigm Shift) is that openness begets innovation, which leads to commercialization, which leads to companies seeking a proprietary edge, until they go too far, close down innovation, and the cycle restarts. It seems to me that openness is characteristic of the early pre-commercial stages of a new industry when many of the participants are in it just for fun; that proprietary advantage is characteristic of the middle phase; and that openness returns in senescent commoditization; which throws open the doors to innovation, and the whole cycle repeats. Here's a crude drawing of the last few cycles in the computer industry:

It was this observation that led me to predict that Web 2.0 companies like Google and Amazon would leverage open source and open standards to build new proprietary companies. This is great unless they get too greedy and use their position to shut down innovation. "This is the thesis scrivened in delight, The reverberating psalm, the right chorale." (Wallace Stevens) There's a repeating cycle of open and proprietary, innovation and exploitation, driven by greed and ignorance overriding joyful exploration. But that exploration can't be denied, and breaks out anew elsewhere once one domain get too fenced in.

The necessary, pragmatic science is to discover the optimum balance between the value we create, and the value we capture. As long as companies create more value than they capture, they create a vibrant ecosystem around them. As soon as they capture more value than they create, they stagnate, however big the bank balance they build up before that becomes apparent.

tags: open source

| comments: 11

| Sphere It

submit: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

0 TrackBacks

TrackBack URL for this entry: http://blogs.oreilly.com/cgi-bin/mt/mt-t.cgi/5195

Comments: 11

Speaking of "true ideas," I am sure Tim knows that there is an even more general theory of innovation than the accurate observations offered in this piece. A key part of that theory is the Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits, which reliably predicts the swings between modular (open source) and interdependent (proprietary) architectures. Application of this theory is essential to the "pragmatic science" needed to set the balance between creating and capturing value. Clayton Christensen explains the prevailing theory of disruptive innovation thoroughly in the fascinating book "The Innovator's Solution."

By the way, Christensen is a brilliant Harvard Business School professor (note that I rarely use the words brilliant and professor in the same sentence). I once heard him quip in a conference speech that he thinks Tim O'Reilly is no dummy (not an exact quote), which I interpret as high praise for Tim's intellect.

I agree with Mr. Drozdov above to some extent, but I would say the next enclosure is proprietary infrastructure. If patents are used to shut down innovation in the next few years, making whole lines of inquiry illegal, then the enclosure is proprietary algorithms, but this would be so devastating for so many businesses that I have hope that the idiocy of the USPTO and others will be curbed by legislative reform driven by savvy lobbies from the business community.

The economies of scale and entrenched ownership of communications infrastructure is the next great challenge - but what form a disruptive technology might take is hard to see. We may see a government-driven annexation of communications infrastructure if the governments are threatened by the Telecoms enough, but that's pretty far-fetched.

Good point, Igor, about proprietary algorithms. I think you may just be right. But I also agree with William that proprietary infrastructure may play a role. (See my post from last summer, Operations: The New Secret Sauce.)

Dennis -- I definitely know about Clayton Christenson's Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits. I use it all the time in my talks. He and I corresponded about it after he read my Open Source Paradigm shift paper, which made his argument, but looking only at a specific instance, where he looks at it occurring across many industries.

Interesting post. I think open data is already on the table, so the "what's next" is more questionable.

My personal take is merging reality with the Net, using RFID and location aware techniques. The various forms of geoscience will enable programmatic reasoning about things in the real world.

This is inherently opposed to the concept of Semantic Web, as that requires computers to understand things about people. Geostuff is only about the computer being able to sense data, then normal programs can run through the usual logic.

Proprietary Algorithms, infrastructure, location aware techniques, programmatic reasoning about things in the real world, can all be summarized as proprietary business processes. Basically Data 2.0 moving to context sensitive distributed workflow of resources.

I would agree, but business process stays within a company. I see that data for things around us will be generally available for computation.

That fits in with open data, as mobs of people can set up workflows for their own interests, rather than needing to attach to a company for a proprietary process.

That's where I spend my time anyway, developing geocontextual applications. That may also be why "Web 2.0" irritates me so much, as I don't see any web browser replacing the stuff I'm writing. :)

"I would agree, but business process stays within a company."

That's true *now*, but I wouldn't count on it remaining so.

The big problem of anticipating what will be proprietary in a world of open data is that it will likely grow out of a reformulation of the societal construct of the corporation as a legal entity.

'Algorithms' might be right, but algorithms might be sophisticated enough by then to qualify as personalities, if not sentients. Will it be a proprietary advantage, or self-determination?

Another route might be a proprietary right to exclude others from some sphere of influence, like a voluntary association. Imagine a SecondLife crowded enough to require filtering of who's avatars you can see and interact with, for example.

While the diagramme is acknowledged as crude, I think there are some significant lacunae in its structure that are easily remedied and would improve the understanding it imparts.

Firstly, all the cycles are represented as the same duration, whereas, without detailed information, I think it intuitively obvious that they are getting shorter and shorter. IBM's reign was much shorter than Microsoft's is, or will be, and Web 2.0 was hardly described before the next cycle was being proposed. I think the same thing is happening to Schumpeter curves.

Secondly, while the peaks are shown as increasing, I suspect the slope should be higher, and perhaps even exponential. They certainly should reflect the Christensen slope of functionality over time.

There is also the fact the view is linear with respect to both integrated (IBM, Microsoft) solutions and the more modular (Open, Web 2.0) solutions (again taken from Christensen's graph), which doesn't begin to represent the overlap that continues for older integrated solutions like IBM, despite their arguable decline in coercive power.

As for What's Next, perhaps the proprietary algorithm (Google PageRank, and all the other SaaS examples) is one, but given they are based on Open alternatives, http://preview.tinyurl.com/2erwlg . I think Tim's observation about Operations (AKA Execution) as the new competitive advantage (AKA Secret Sauce) is probably, hopefully correct.

Consumers/Producers can then look forward to less enclosure, except by delight.

How that will suit the comfortable incumbents, previously protected in their cost of entry walled gardens, can be easily imagined.

analyzing the individual curves & cases is far less important than the larger cross-cycle trend. that analysis proves straightforward: whats next, the next cycle, is always result of a disruptive innovation against the pinnacle of the current cycle. that there are significant numbers of times this disruption occurs by open source, and signficant numbers of time this disruption comes from corporate. whether its open source or proprietary is not particularly relevant, so long as disruption is continually happening. this is really a deleuzian dialect here, individual singularities folding into entirely new virtualities through time. disruption begets the next disruptions.

to look at this extended sequence of disruption after disruption and say that a companies downfall is becoming overly propriteary is a pretty nitpicky and exact trend to converge on. on the surface, survival is much simpler. those who can continue disruptive innovating and responding survive, and everything else is doomed to eventual obsolescence. it just so happens that corporate ability to remain disruptive and innovative -- while maintaining profitability -- is a sigificantly different job than people mucking around for the fun of it.

we havent hit the real exponential growth: when people realize its fun to meddle with technology, and that it can be free and extemporaneous and novel. go make faire. ;)

Just to clear something up:

"True ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate and verify. False ideas are those that we can not. That is the practical difference it makes to us to have true ideas.

This is illogical, intellectually barren and philosophically lazy.

Fermat's last theorem was true, despite the fact that for many years it could not be validated, corroborated or verified. When it was proved, it didn't suddenly switch from being a falsehood to being true - it was always true, it just gained a proof.

People mix up proofs and truths all the time. You can only prove those things that are true, but there are some things which are true that have no proof.

At the risk of being needlessly controversial (although why people always argue with me on this, I have no idea: they clearly haven't read any books on logic, or at least understood them), this is the logical flaw most atheists fall into: "There is no proof for God, therefore logic dictates he must not exist".

In fact, logic alone would lead to "Because of the nature of God as described by theists, proof is impossible in this Universe, and therefore logic dictates we can never know if he exists or not, everything else is faith, and my belief is on a balance of probabilities, he doesn't". God might exist without proof. He might not exist, but he'll have to carry on existing without proof too. Neither argument can assert 'truth', merely belief. Proofs rely on truths, truths don't care about proofs.

Bringing this back to the topic of the conversation on open source. Yes, I believe open source works. My entire business plan this year is to build on a series of open source releases. That said, I think it works right now - I can not assert, because I have no proof, it will always work. I think "What's next?" is answered as "open source", but I can't agree that this will continue for the rest of time. New models that we can't even conceive of right now will emerge and challenge open source. Don't bank on it working for ever, but I think it will come to dominate the next 30 years, and that's long enough for us to worry about for now.

Post A Comment:

STAY CONNECTED

RECENT COMMENTS

- Paul Robinson on Open Source and William James: Just to clear something...

- rektide on Open Source and William James: analyzing the individua...

- Hamish MacEwan on Open Source and William James: While the diagramme is ...

- Michael Bernstein on Open Source and William James: "I would agree, but bus...

- steve on Open Source and William James: I would agree, but busi...

- Guy on Open Source and William James: Proprietary Algorithms,...

- steve on Open Source and William James: Interesting post. I thi...

- Tim O'Reilly on Open Source and William James: Good point, Igor, about...

- William on Open Source and William James: I agree with Mr. Drozdo...

- Dennis Linnell on Open Source and William James: Speaking of "true ideas...

Igor Drozdov [01.30.07 05:30 AM]

One thought regarding the chart above that says "What's next?"

I think it's going to be Open Data, Proprietary Algorithms. Google and its proprietary method to search open data is one example. The rush to patent every business or software process under the sun is another example of this emerging trend.