Bob Quinn, one of the top AT&T lobbyists ("Senior Vice President-Federal Regulatory") in a company famous for lobbyists, must have drawn the short straw at the office staff meeting this week, because he got a truly unenviable job. Quinn's task was to explain to the world how AT&T's plan to keep blocking FaceTime video chats on some data plans but to unblock it on others was a good thing for customers, how AT&T was in "a learning mode," and—most importantly—why the decision was absolutely, completely legal despite what the unwashed peasants in "public advocacy" work would have you believe.

So Quinn walked down the hall to the closet next to the photocopier and pulled out something reserved for just such an occasion: the company's sole suit of adamantine armor, fortified against flame attacks by a special concoction distilled from the rage of 10,000 Internet commenters. (We are, admittedly, hypothesizing a bit at this point.) Bold Sir Quinn donned the suit and sallied forth to his desk, where he sharpened his quill pen and churned out a corporate blog post on "enabling" FaceTime for AT&T users.

In it, Quinn pointed out that AT&T's serfs customers could continue to use FaceTime over WiFi. With iOS 6, they can soon use FaceTime over the cell network, too, but only with certain data plans. On other plans, FaceTime wouldn't work. The restrictions apply only to FaceTime, however; Quinn even suggests that aggrieved users go out and download any other video chat app from the App Store—and they can run it on any data plan without problems.

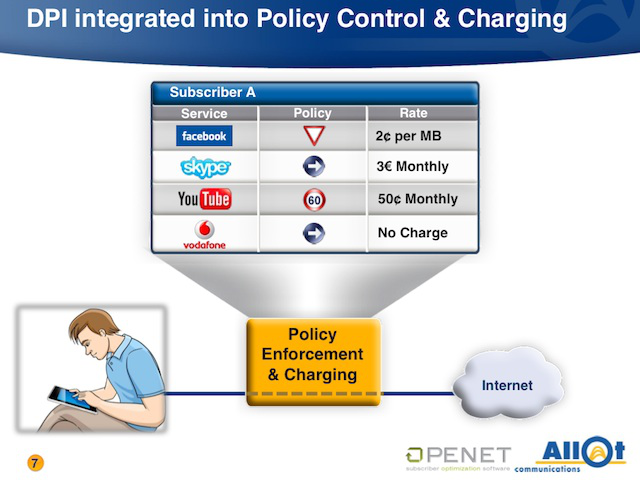

The distinctions being drawn seem bizarre and arbitrary to many customers who argue that data is data—I paid for it and should control what I use it on, not AT&T. It's even stranger because AT&T isn't targeting "video chat" apps with its restriction; it is only targeting FaceTime.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...