In one of more impressive hacks in recent memory, researchers have devised an attack that exploits physical weaknesses in certain types of DDR memory chips to elevate the system rights of untrusted users of Intel-compatible PCs running Linux.

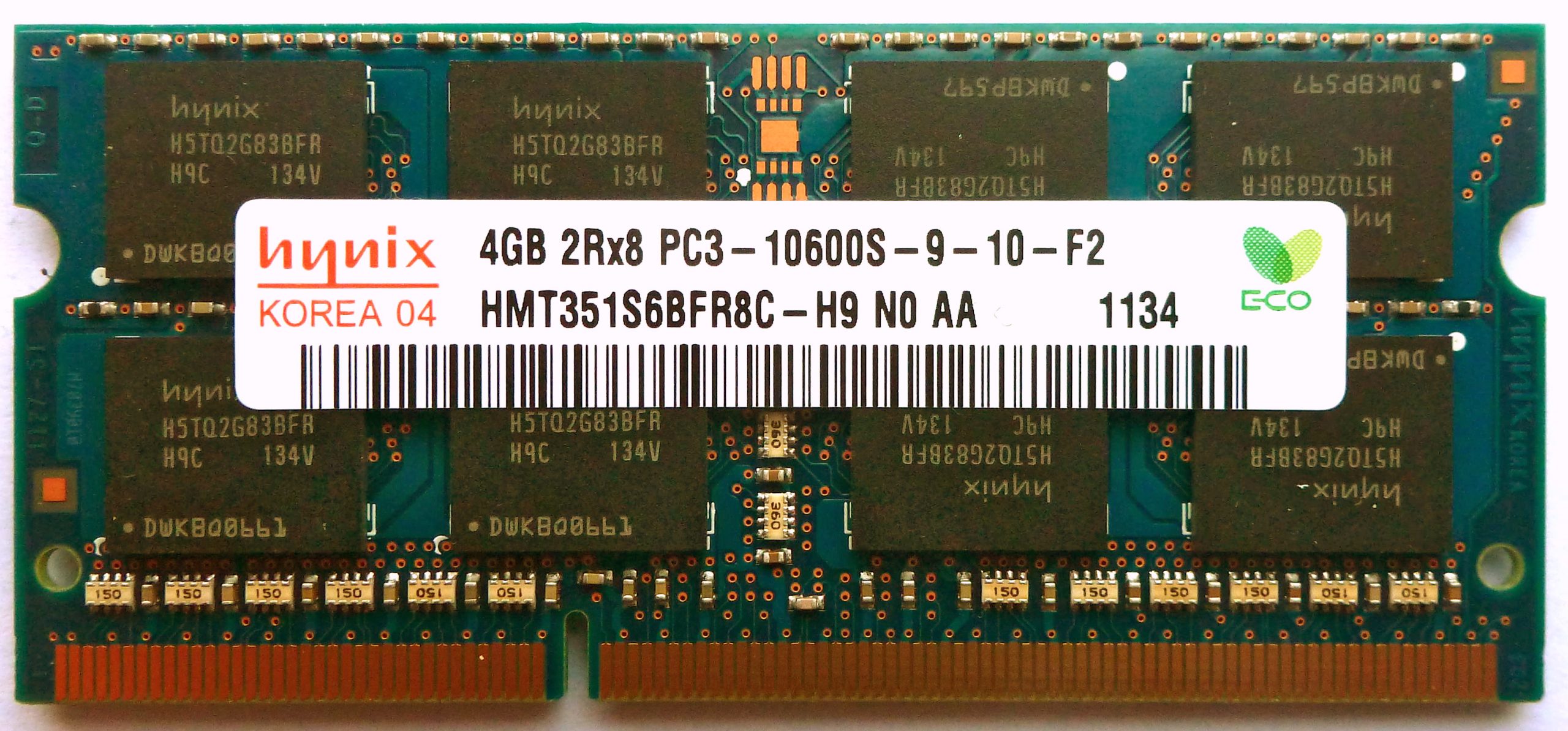

The technique, outlined in a blog post published Monday by Google's Project Zero security initiative, works by reversing individual bits of data stored in DDR3 chip modules known as DIMMs. Last year, scientists proved that such "bit flipping" could be accomplished by repeatedly accessing small regions of memory, a feat that—like a magician who transforms a horse into a rabbit—allowed them to change the value of contents stored in computer memory. The research unveiled Monday showed how to fold such bit flipping into an actual attack.

"The thing that is really impressive to me in what we see here is in some sense an analog- and manufacturing-related bug that is potentially exploitable in software," David Kanter, senior editor of the Microprocessor Report, told Ars. "This is reaching down into the underlying physics of the hardware, which from my standpoint is cool to see. In essence, the exploit is jumping several layers of the stack."

Getting hammered

DDR memory is laid out in an array of rows and columns, which are assigned in large blocks to various applications and operating system resources. To protect the integrity and security of the entire system, each large chunk of memory is contained in a "sandbox" that can be accessed only by a given app or OS process. Bit flipping works when a hacker-developed app or process accesses two carefully selected rows of memory hundreds of thousands of times in a tiny fraction of a second. By hammering the two "aggressor" memory regions, the exploit can reverse one or more bits in a third "victim" location. In other words, selected zeros in the victim region will turn into ones or vice versa.

The ability to alter the contents of forbidden memory regions has far-reaching consequences. It can allow a user or application who has extremely limited system privileges to gain unfettered administrative control. From there, a hacker may be able to execute malicious code or hijack the operations of other users or software programs. Such elevation-of-privilege hacks are especially potent on servers available in data centers that are available to multiple customers.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...