Valve didn’t give itself an easy job when it publicly announced its decision, over two years ago now, to bring the PC gaming experience to the living room TV. Plenty of companies have tried, and most never even got off the ground (see the Infinium Phantom for just one high-profile failure). But Valve is perhaps better positioned for success than any past effort, with a deep understanding of the PC gaming market and a deeply entrenched, market-leading distribution platform in Steam.

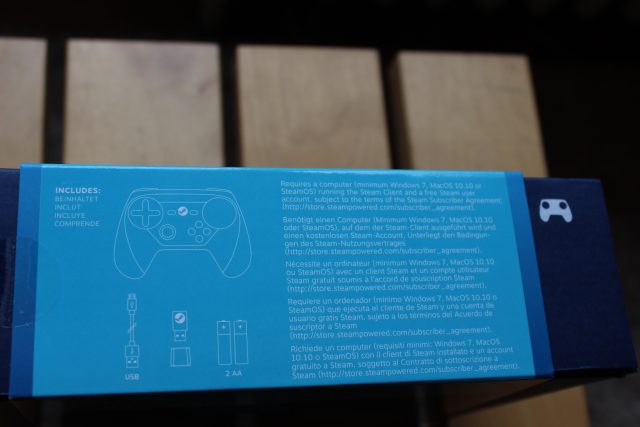

Now after a few delays and a soft launch for the OS, Valve is poised to officially launch its run at console gaming. Steam hardware will ship to pre-orderers this week and to others (including select retailers like GameStop) on November 10. It's a multi-pronged effort that includes a lot of moving parts: the SteamOS operating system; the partner-produced "Steam Machine" hardware designed to run that OS out of the box; the Valve-produced Steam Link box that allows for basic in-home streaming; and the Steam Controller meant to make it all controllable from a keyboard-and-mouse-free couch.

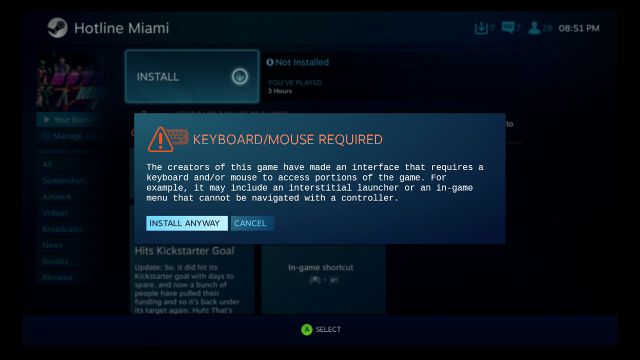

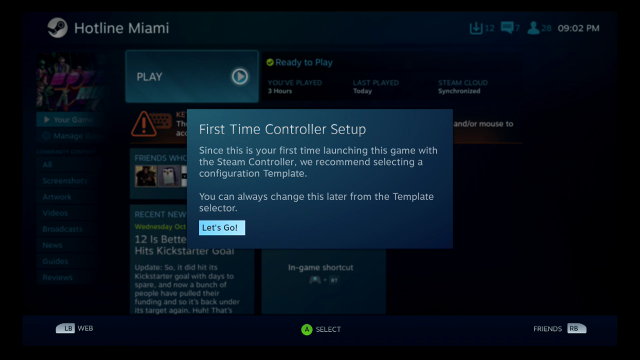

We've been putting that entire ecosystem through its paces for a few days now, and while some of those pieces work better than others, all have some trouble living up to the promise of a seamless, hassle-free, PC-on-a-TV-console experience. It's early, and Valve's attack on the living room is far from a vaporware failure, but it's not a shock-and-awe knockout blitz either.

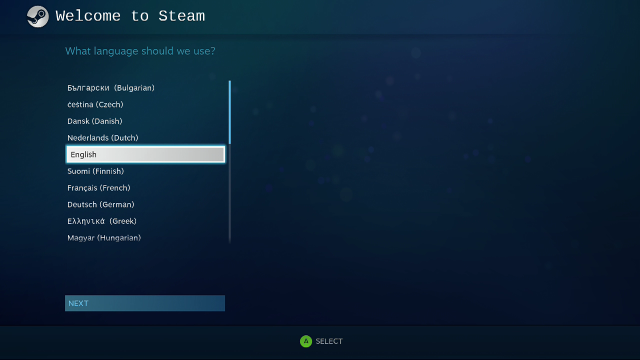

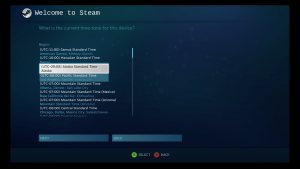

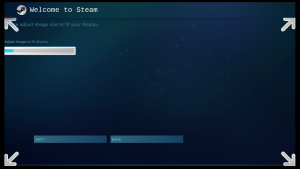

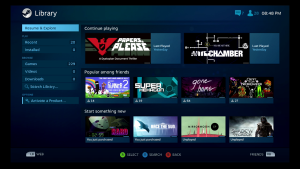

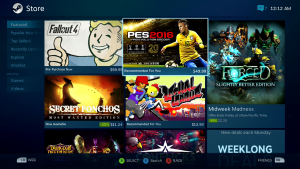

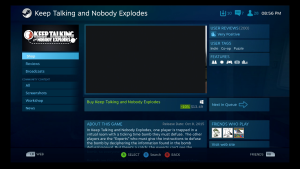

SteamOS: Familiar in a Big Picture sense

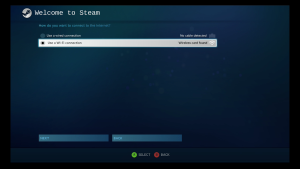

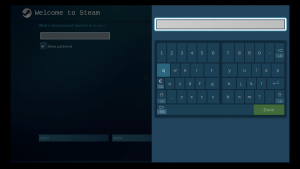

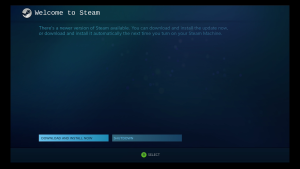

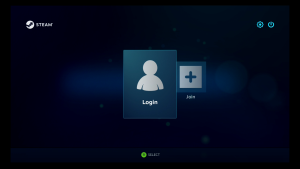

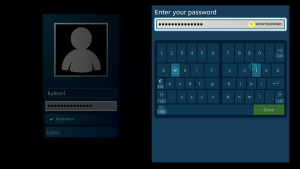

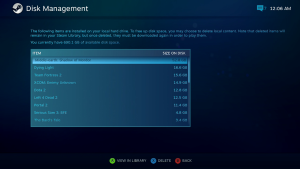

SteamOS itself does a good job of hiding its Linux roots, and we mean that in the best possible way. There are no command lines to struggle with or repos to download or drivers to configure when you first load up a SteamOS system. Instead, Steam’s own front end guides you through a painless setup process that’s not unlike that of the console competition. If you didn’t know any better, you might not even be aware that the Steam Machine is an actual computer with upgradeable hardware, direct access to the file system, and other such PC niceties.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...