Understanding the difference between sudo and su command on Linux

In one of our earlier articles, we discussed the 'sudo' command in detail. Towards the ends of that tutorial, there was a mention of another similar command 'su' in a small note. Well, in this article, we will discuss in detail the 'su' command as well as how it differs from the 'sudo' command.

But before we do that, please note that all the instructions and examples mentioned in this tutorial have been tested on Ubuntu 18.04 LTS and Debian 10.

The su command in Linux

The main work of the su command is to let you switch to some other user during a login session. In other words, the tool lets you assume the identity of some other user without having to logout and then login (as that user).

The su command is mostly used to switch to the superuser/root account (as root privileges are frequently required while working on the command line), but - as already mentioned - you can use it to switch to any other, non-root user as well.

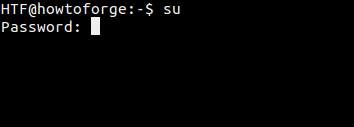

Here's how you can use this command to switch to the root user:

The password that this command requires is also of the root user. So in general, the su command requires you to enter the password of the target user. After the correct password is entered, the tool starts a sub-session inside the existing session on the terminal.

su -

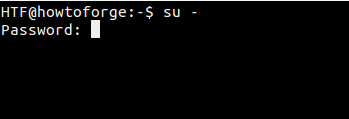

There's another way to switch to the root user: run the 'su -' command:

Now, what's the difference between 'su' and 'su -' ? Well, the former keeps the environment of the old/original user even after the switch to root has been made, while the latter creates a new environment (as dictated by the ~/.bashrc of the root user), similar to the case when you explicitly log in as root user from the log-in screen.

IMPORTANT for Debian 10 users. The PATH variable of the root user differs on Debian 10 when using 'su' vs 'su -', directories like /sbin are missing when only 'su' is used which means that you might get command not found errors even for basic system administration commands. So always use 'su -' on Debian 10 to become root user.

The man page of 'su' also makes it clear:

The optional argument - may be used to provide an environment similar to what the user would expect had the user logged in directly.

So, you'll agree that logging in with 'su -' makes more sense. But as the 'su' command also exists, one might wonder when that's useful. The following excerpt - taken from the ArchLinux wiki website - gives a good idea about the benefits and pitfalls of the 'su' command:

- It sometimes can be advantageous for a system administrator to use the shell account of an ordinary user rather than its own. In particular, occasionally the most efficient way to solve a user's problem is to log into that user's account in order to reproduce or debug the problem.

- However, in many situations it is not desirable, or it can even be dangerous, for the root user to be operating from an ordinary user's shell account and with that account's environmental variables rather than from its own. While inadvertently using an ordinary user's shell account, root could install a program or make other changes to the system that would not have the same result as if they were made while using the root account. For instance, a program could be installed that could give the ordinary user power to accidentally damage the system or gain unauthorized access to certain data.

Note: In case you want to pass more arguments after - in 'su -', then you should use the -l command line option that the command offers (instead of -). Here's the definition of - and the -l command line option:

-, -l, --login

Provide an environment similar to what the user would expect had the user logged in directly.

When - is used, it must be specified as the last su option. The other forms (-l and --login) do not have this restriction.

su -c

There's another option of the 'su' command that's worth mentioning: -c. It lets you provide a command that you want to run after switching to the target user.

The man page of 'su' explains it as:

-c, --command COMMAND

Specify a command that will be invoked by the shell using its -c.

The executed command will have no controlling terminal. This option cannot be used to execute interactive programs which need a controlling TTY.

Consider the following example template:

su [target-user] -c [command-to-run]

So in this case, the 'command-to-run' will be executed as:

[shell] -c [command-to-run]

Where 'shell' would be replaced by 'target-user' shell defined in the /etc/passwd file.

Sudo vs Su

Now since we have discussed the basics of the 'su' command as well, it's time we discuss the differences between the 'sudo' and the 'su' commands.

Password

The primary difference between the two is the password they require: while 'sudo' requires current user's password, 'su' requires you to enter the root user password.

Quite clearly, 'sudo' is a better alternative between the two as far as security is concerned. For example, consider the case of computer being used by multiple users who also require root access. Using 'su' in such a scenario means sharing the root password with all of them, which is not a good practice in general.

Moreover, in case you want to revoke the superuser/root access of a particular user, the only way is to change the root password and then redistribute the new root password among all the other users.

With Sudo, on the other hand, you can handle both these scenarios effortlessly. Given that 'sudo' requires users to enter their own password, you don't need to share the root password will all the users in the first place. And to stop a particular user from accessing root privileges, all you have to do is to tweak the corresponding entry in the 'sudoers' file.

Default behavior

The other difference between the two commands is in their default behavior. While 'sudo' only allows you to run a single command with elevated privileges, the 'su' command launches a new shell, allowing you to run as many commands as you want with root privileges until you explicitly exit that sell.

So the default behavior of the 'su' command is potentially dangerous given the possibility that the user can forget the fact that they are working as root, and might inadvertently make some irrecoverable changes (such as run the 'rm -rf' command in wrong directory). For a detailed discussion on why it's not encouraged to always work as root, head here.

Logging

Although commands run through 'sudo' are executed as the target user (which is 'root' by default), they are tagged with the sudoer's user-name. But in case of 'su', it's not possible to directly trace what a user did after they su'd to the root account.

Flexibility

The 'sudo' command is far more flexible in that you can even limit the commands that you want the sudo-ers to have access to. In other words, users with access to 'sudo' can only be given access to commands that are required for their job. However, with 'su' that's not possible - either you have the privilege to do everything or nothing.

Sudo su

Presumably due to the potential risks involved with using 'su' or logging directly as root, some Linux distributions - like Ubuntu - disable the root user account by default. Users are encouraged to use 'sudo' whenever they need root privileges.

However, you can still do 'su' successfully, i.e, without entering the root password. All you need to do is to run the following command:

sudo su

Since you're running the command with 'sudo', you'll only be required to enter your password. So once that is done, the 'su' command will be run as root, meaning it won't ask for any passwords.

PS: In case you want to enable the root account on your system (although that's strongly discouraged because you can always use 'sudo' or 'sudo su'), you'll have to set the root password manually, which you can do that using the following command:

sudo passwd root

Conclusion

Both this as well as our previous tutorial (which focuses on 'sudo') should give you a good idea about the available tools that let you do tasks that require escalated (or a completely different set of) privileges. In case you have something to share about 'su' or 'sudo', or want to share your own experience, you are welcome to do that in the comments below.