Memory part 6: More things programmers can do

| This article brought to you by LWN subscribers Subscribers to LWN.net made this article — and everything that surrounds it — possible. If you appreciate our content, please buy a subscription and make the next set of articles possible. |

[Editor's note: this is part 6 of Ulrich Drepper's "What every programmer should know about memory"; this part contains the second half of section 6, covering the optimization of multi-threaded code. The first half of this section was published in part 5; please see part 1 for pointers to the other sections.]

6.4 Multi-Thread Optimizations

When it comes to multi-threading, there are three different aspects of cache use which are important:

- Concurrency

- Atomicity

- Bandwidth

These aspects also apply to multi-process situations but, because multiple processes are (mostly) independent, it is not so easy to optimize for them. The possible multi-process optimizations are a subset of those available for the multi-thread scenario. So we will deal exclusively with the latter here.

Concurrency in this context refers to the memory effects a process experiences when running more than one thread at a time. A property of threads is that they all share the same address space and, therefore, can all access the same memory. In the ideal case, the memory regions used by the threads are distinct, in which case those threads are coupled only lightly (common input and/or output, for instance). If more than one thread uses the same data, coordination is needed; this is when atomicity comes into play. Finally, depending on the machine architecture, the available memory and inter-processor bus bandwidth available to the processors is limited. We will handle these three aspects separately in the following sections—although they are, of course, closely linked.

6.4.1 Concurrency Optimizations

Initially, in this section, we will discuss two separate issues which actually require contradictory optimizations. A multi-threaded application uses common data in some of its threads. Normal cache optimization calls for keeping data together so that the footprint of the application is small, thus maximizing the amount of memory which fits into the caches at any one time.

There is a problem with this approach, though: if multiple threads write to a memory location, the cache line must be in ‘E’ (exclusive) state in the L1d of each respective core. This means that a lot of RFO requests are sent, in the worst case one for each write access. So a normal write will be suddenly very expensive. If the same memory location is used, synchronization is needed (maybe through the use of atomic operations, which is handled in the next section). The problem is also visible, though, when all the threads are using different memory locations and are supposedly independent.

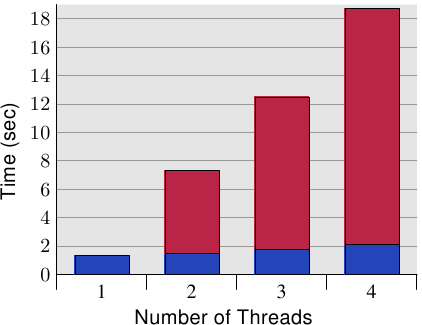

Figure 6.10: Concurrent Cache Line Access Overhead

Figure 6.10 shows the results of this “false sharing”. The test program (shown in Section 9.3) creates a number of threads which do nothing but increment a memory location (500 million times). The measured time is from the program start until the program finishes after waiting for the last thread. The threads are pinned to individual processors. The machine has four P4 processors. The blue values represent runs where the memory allocations assigned to each thread are on separate cache lines. The red part is the penalty occurred when the locations for the threads are moved to just one cache line.

The blue measurements (when using individual cache lines) match what one would expect. The program scales without penalty to many threads. Each processor keeps its cache line in its own L1d and there are no bandwidth issues since not much code or data has to be read (in fact, it is all cached). The measured slight increase is really system noise and probably some prefetching effects (the threads use sequential cache lines).

The measured overhead, computed by dividing the time needed when using one cache line versus a separate cache line for each thread, is 390%, 734%, and 1,147% respectively. These large numbers might be surprising at first sight but, when thinking about the cache interaction needed, it should be obvious. The cache line is pulled from one processor's cache just after it has finished writing to the cache line. All processors, except the one which has the cache line at any given moment, are delayed and cannot do anything. Each additional processor will just cause more delays.

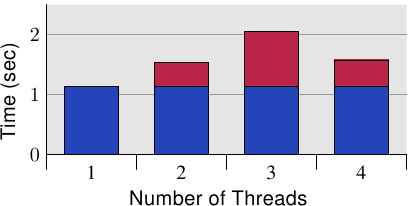

It is clear from these measurements that this scenario must be avoided in programs. Given the huge penalty, this problem is, in many situations, obvious (profiling will show the code location, at least) but there is a pitfall with modern hardware. Figure 6.11 shows the equivalent measurements when running the code on a single processor, quad core machine (Intel Core 2 QX 6700). Even with this processor's two separate L2s the test case does not show any scalability issues. There is a slight overhead when using the same cache line more than once but it does not increase with the number of cores. {I cannot explain the lower number when all four cores are used but it is reproducible.} If more than one of these processors were used we would, of course, see results similar to those in Figure 6.10. Despite the increasing use of multi-core processors, many machines will continue to use multiple processors and, therefore, it is important to handle this scenario correctly, which might mean testing the code on real SMP machines.

Figure 6.11: Overhead, Quad Core

There is a very simple “fix” for the problem: put every variable on its own cache line. This is where the conflict with the previously mentioned optimization comes into play, specifically, the footprint of the application would increase a lot. This is not acceptable; it is therefore necessary to come up with a more intelligent solution.

What is needed is to identify which variables are used by only one thread at a time, those used by only one thread ever, and maybe those which are contested at times. Different solutions for each of these scenarios are possible and useful. The most basic criterion for the differentiation of variables is: are they ever written to and how often does this happen.

Variables which are never written to and those which are only initialized once are basically constants. Since RFO requests are only needed for write operations, constants can be shared in the cache (‘S’ state). So, these variables do not have to be treated specially; grouping them together is fine. If the programmer marks the variables correctly with const, the tool chain will move the variables away from the normal variables into the .rodata (read-only data) or .data.rel.ro (read-only after relocation) section {Sections, identified by their names are the atomic units containing code and data in an ELF file.} No other special action is required. If, for some reason, variables cannot be marked correctly with const, the programmer can influence their placement by assigning them to a special section.

When the linker constructs the final binary, it first appends the sections with the same name from all input files; those sections are then arranged in an order determined by the linker script. This means that, by moving all variables which are basically constant but are not marked as such into a special section, the programmer can group all of those variables together. There will not be a variable which is often written to between them. By aligning the first variable in that section appropriately, it is possible to guarantee that no false sharing happens. Assume this little example:

int foo = 1;

int bar __attribute__((section(".data.ro"))) = 2;

int baz = 3;

int xyzzy __attribute__((section(".data.ro"))) = 4;

If compiled, this input file defines four variables. The interesting part is that the variables foo and baz, and bar and xyzzy are grouped together respectively. Without the attribute definitions the compiler would allocate all four variables in the sequence in which they are defined in the source code the a section named .data. {This is not guaranteed by the ISO C standard but it is how gcc works.} With the code as-is the variables bar and xyzzy are placed in a section named .data.ro. The section name .data.ro is more or less arbitrary. A prefix of .data. guarantees that the GNU linker will place the section together with the other data sections.

The same technique can be applied to separate out variables which are mostly read but occasionally written. Simply choose a different section name. This separation seems to make sense in some cases like the Linux kernel.

If a variable is only ever used by one thread, there is another way to specify the variable. In this case it is possible and useful to use thread-local variables (see [mytls]). The C and C++ language in gcc allow variables to be defined as per-thread using the __thread keyword.

int foo = 1; __thread int bar = 2; int baz = 3; __thread int xyzzy = 4;

The variables bar and xyzzy are not allocated in the normal data segment; instead each thread has its own separate area where such variables are stored. The variables can have static initializers. All thread-local variables are addressable by all other threads but, unless a thread passes a pointer to a thread-local variable to those other threads, there is no way the other threads can find that variable. Due to the variable being thread-local, false sharing is not a problem—unless the program artificially creates a problem. This solution is easy to set up (the compiler and linker do all the work), but it has its cost. When a thread is created, it has to spend some time on setting up the thread-local variables, which requires time and memory. In addition, addressing thread-local variables is usually more expensive than using global or automatic variables (see [mytls] for explanations of how the costs are minimized automatically, if possible).

One drawback of using thread-local storage (TLS) is that, if the use of the variable shifts over to another thread, the current value of the variable in the old thread is not available to new thread. Each thread's copy of the variable is distinct. Often this is not a problem at all and, if it is, the shift over to the new thread needs coordination, at which time the current value can be copied.

A second, bigger problem is possible waste of resources. If only one thread ever uses the variable at any one time, all threads have to pay a price in terms of memory. If a thread does not use any TLS variables, the lazy allocation of the TLS memory area prevents this from being a problem (except for TLS in the application itself). If a thread uses just one TLS variable in a DSO, the memory for all the other TLS variables in this object will be allocated, too. This could potentially add up if TLS variables are used on a large scale.

In general the best advice which can be given is

- Separate at least read-only (after initialization) and

read-write variables. Maybe extend this separation to read-mostly variables as a

third category.

- Group read-write variables which are used together into a

structure. Using a structure is the only way to ensure the memory

locations for all of those variables are close together in a way which is translated

consistently by all gcc versions..

- Move read-write variables which are often written to by

different threads onto their own cache line. This might mean adding

padding at the end to fill a remainder of the cache line. If

combined with step 2, this is often not really wasteful. Extending

the example above, we might end up with code as follows (assuming

bar and xyzzy are meant to be used together):

int foo = 1; int baz = 3; struct { struct al1 { int bar; int xyzzy; }; char pad[CLSIZE - sizeof(struct al1)]; } rwstruct __attribute__((aligned(CLSIZE))) = { { .bar = 2, .xyzzy = 4 } };Some code changes are needed (references to bar have to be replaced with rwstruct.bar, likewise for xyzzy) but that is all. The compiler and linker do all the rest. {This code has to be compiled with -fms-extensions} on the command line.}

- If a variable is used by multiple threads, but every use is

independent, move the variable into TLS.

6.4.2 Atomicity Optimizations

If multiple threads modify the same memory location concurrently, processors do not guarantee any specific result. This is a deliberate decision made to avoid costs which are unnecessary in 99.999% of all cases. For instance, if a memory location is in the ‘S’ state and two threads concurrently have to increment its value, the execution pipeline does not have to wait for the cache line to be available in the ‘E’ state before reading the old value from the cache to perform the addition. Instead it reads the value currently in the cache and, once the cache line is available in state ‘E’, the new value is written back. The result is not as expected if the two cache reads in the two threads happen simultaneously; one addition will be lost.

To assure this does not happen, processors provide atomic operations. These atomic operations would, for instance, not read the old value until it is clear that the addition could be performed in a way that the addition to the memory location appears as atomic. In addition to waiting for other cores and processors, some processors even signal atomic operations for specific addresses to other devices on the motherboard. All this makes atomic operations slower.

Processor vendors decided to provide different sets of atomic operations. Early RISC processors, in line with the ‘R’ for reduced, provided very few atomic operations, sometimes only an atomic bit set and test. {HP Parisc still does not provide more…} At the other end of the spectrum, we have x86 and x86-64 which provide a large number of atomic operations. The generally available atomic operations can be categorized in four classes:

- Bit Test

- These operations set or clear a bit atomically and return a status indicating whether the bit was set before or not.

- Load Lock/Store Conditional (LL/SC)

-

{Some people use

“linked” instead of “lock”, it is all the same.}

These operations work as a pair where the special load instruction is used to start an transaction and the final store will only succeed if the location has not been modified in the meantime. The store operation indicates success or failure, so the program can repeat its efforts if necessary.

- Compare-and-Swap (CAS)

- This is a ternary operation which writes a value provided as a parameter into an address (the second parameter) only if the current value is the same as the third parameter value;

- Atomic Arithmetic

- These operations are only available on x86 and x86-64, which can perform arithmetic and logic operations on memory locations. These processors have support for non-atomic versions of these operations but RISC architectures do not. So it is no wonder that their availability is limited.

An architecture supports either the LL/SC or the CAS instruction, not both. Both approaches are basically equivalent; they allow the implementation of atomic arithmetic operations equally well, but CAS seems to be the preferred method these days. All other operations can be indirectly implemented using it. For instance, an atomic addition:

int curval;

int newval;

do {

curval = var;

newval = curval + addend;

} while (CAS(&var, curval, newval));

The result of the CAS call indicates whether the operation succeeded or not. If it returns failure (non-zero value), the loop is run again, the addition is performed, and the CAS call is tried again. This repeats until it is successful. Noteworthy about the code is that the address of the memory location has to be computed in two separate instructions. {The CAS opcode on x86 and x86-64 can avoid the load of the value in the second and later iterations but, on this platform, we can write the atomic addition in a simpler way, with a single addition opcode.} For LL/SC the code looks about the same.

int curval;

int newval;

do {

curval = LL(var);

newval = curval + addend;

} while (SC(var, newval));

Here we have to use a special load instruction (LL) and we do not have to pass the current value of the memory location to SC since the processor knows if the memory location has been modified in the meantime.

The big differentiators are x86 and x86-64 where we have the atomic operations and, here, it is important to select the proper atomic operation to achieve the best result. Figure 6.12 shows three different ways to implement an atomic increment operation.

All three produce different code on x86 and x86-64 while the code might be identical on other architectures. There are huge performance differences. The following table shows the execution time for 1 million increments by four concurrent threads. The code uses the built-in primitives of gcc (__sync_*).

for (i = 0; i < N; ++i) __sync_add_and_fetch(&var,1);1. Add and Read Result

for (i = 0; i < N; ++i) __sync_fetch_and_add(&var,1);2. Add and Return Old Value

for (i = 0; i < N; ++i) { long v, n; do { v = var; n = v + 1; } while (!__sync_bool_compare_and_swap(&var, v, n)); }3. Atomic Replace with New Value

Figure 6.12: Atomic Increment in a Loop

1. Exchange Add 2. Add Fetch 3. CAS 0.23s 0.21s 0.73s

The first two numbers are similar; we see that returning the old value is a little bit faster. The important piece of information is the highlighted field, the cost when using CAS. It is, unsurprisingly, a lot more expensive. There are several reasons for this: 1. there are two memory operations, 2. the CAS operation by itself is more complicated and requires even conditional operation, and 3. the whole operation has to be done in a loop in case two concurrent accesses cause a CAS call to fail.

Now a reader might ask a question: why would somebody use the complicated and longer code which utilizes CAS? The answer to this is: the complexity is usually hidden. As mentioned before, CAS is currently the unifying atomic operation across all interesting architectures. So some people think it is sufficient to define all atomic operations in terms of CAS. This makes programs simpler. But as the numbers show, the results can be everything but optimal. The memory handling overhead of the CAS solution is huge. The following illustrates the execution of just two threads, each on its own core.

Thread #1 Thread #2 var Cache State v = var ‘E’ on Proc 1 n = v + 1 v = var ‘S’ on Proc 1+2 CAS(var) n = v + 1 ‘E’ on Proc 1 CAS(var) ‘E’ on Proc 2

We see that, within this short period of execution, the cache line status changes at least three times; two of the changes are RFOs. Additionally, the second CAS will fail, so that thread has to repeat the whole operation. During that operation the same can happen again.

In contrast, when the atomic arithmetic operations are used, the processor can keep the load and store operations needed to perform the addition (or whatever) together. It can ensure that concurrently-issued cache line requests are blocked until the atomic operation is done. Each loop iteration in the example therefore results in, at most, one RFO cache request and nothing else.

What all this means is that it is crucial to define the machine abstraction at a level at which atomic arithmetic and logic operations can be utilized. CAS should not be universally used as the unification mechanism.

For most processors, the atomic operations are, by themselves, always atomic. One can avoid them only by providing completely separate code paths for the case when atomicity is not needed. This means more code, a conditional, and further jumps to direct execution appropriately.

For x86 and x86-64 the situation is different: the same instructions can be used in both atomic and non-atomic ways. To make them atomic, a special prefix for the instruction is used: the lock prefix. This opens the door for atomic operations to avoid the high costs if the atomicity requirement in a given situation is not needed. Generic code in libraries, for example, which always has to be thread-safe if needed, can benefit from this. No information is needed when writing the code, the decision can be made at runtime. The trick is to jump over the lock prefix. This trick applies to all the instructions which the x86 and x86-64 processor allow to prefix with lock.

cmpl $0, multiple_threads

je 1f

lock

1: add $1, some_var

If this assembler code appears cryptic, do not worry, it is simple. The first instruction checks whether a variable is zero or not. Nonzero in this case indicates that more than one thread is running. If the value is zero, the second instruction jumps to label 1. Otherwise, the next instruction is executed. This is the tricky part. If the je instruction does not jump, the add instruction is executed with the lock prefix. Otherwise it is executed without the lock prefix.

Adding a relatively expensive operation like a conditional jump (expensive in case the branch prediction fails) seems to be counter productive. Indeed it can be: if multiple threads are running most of the time, the performance is further decreased, especially if the branch prediction is not correct. But if there are many situations where only one thread is in use, the code is significantly faster. The alternative of using an if-then-else construct introduces an additional unconditional jump in both cases which can be slower. Given that an atomic operation costs on the order of 200 cycles, the cross-over point for using the trick (or the if-then-else block) is pretty low. This is definitely a technique to be kept in mind. Unfortunately this means gcc's __sync_* primitives cannot be used.

6.4.3 Bandwidth Considerations

When many threads are used, and they do not cause cache contention by using the same cache lines on different cores, there still are potential problems. Each processor has a maximum bandwidth to the memory which is shared by all cores and hyper-threads on that processor. Depending on the machine architecture (e.g., the one in Figure 2.1), multiple processors might share the same bus to memory or the Northbridge.

The processor cores themselves run at frequencies where, at full speed, even in perfect conditions, the connection to the memory cannot fulfill all load and store requests without waiting. Now, further divide the available bandwidth by the number of cores, hyper-threads, and processors sharing a connection to the Northbridge and suddenly parallelism becomes a big problem. Programs which are, in theory, very efficient may be limited by the memory bandwidth.

In Figure 3.32 we have seen that increasing the FSB speed of a processor can help a lot. This is why, with growing numbers of cores on a processor, we will also see an increase in the FSB speed. Still, this will never be enough if the program uses large working sets and it is sufficiently optimized. Programmers have to be prepared to recognize problems due to limited bandwidth.

The performance measurement counters of modern processors allow the observation of FSB contention. On Core 2 processors the NUS_BNR_DRV event counts the number of cycles a core has to wait because the bus is not ready. This indicates that the bus is highly used and loads from or stores to main memory take even longer than usual. The Core 2 processors support more events which can count specific bus actions like RFOs or the general FSB utilization. The latter might come in handy when investigating the possibility of scalability of an application during development. If the bus utilization rate is already close to 1.0 then the scalability opportunities are minimal.

If a bandwidth problem is recognized, there are several things which can be done. They are sometimes contradictory so some experimentation might be necessary. One solution is to buy faster computers, if there are some available. Getting more FSB speed, faster RAM modules, and possibly memory local to the processor, can—and probably will—help. It can cost a lot, though. If the program in question is only needed on one (or a few machines) the one-time expense for the hardware might cost less than reworking the program. In general, though, it is better to work on the program.

After optimizing the program itself to avoid cache misses, the only option left to achieve better bandwidth utilization is to place the threads better on the available cores. By default, the scheduler in the kernel will assign a thread to a processor according to its own policy. Moving a thread from one core to another is avoided when possible. The scheduler does not really know anything about the workload, though. It can gather information from cache misses etc but this is not much help in many situations.

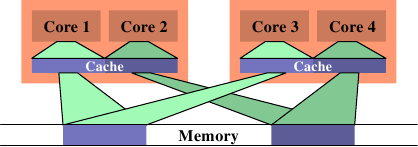

Figure 6.13: Inefficient Scheduling

One situation which can cause big FSB usage is when two threads are scheduled on different processors (or cores which do not share a cache) and they use the same data set. Figure 6.13 shows such a situation. Core 1 and 3 access the same data (indicated by the same color for the access indicator and the memory area). Similarly core 2 and 4 access the same data. But the threads are scheduled on different processors. This means each data set has to be read twice from memory. This situation can be handled better.

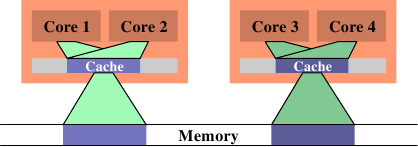

Figure 6.14: Efficient Scheduling

In Figure 6.14 we see how it should ideally look like. Now the total cache size in use is reduced since now core 1 and 2 and core 3 and 4 work on the same data. The data sets have to be read from memory only once.

This is a simple example but, by extension, it applies to many situations. As mentioned before, the scheduler in the kernel has no insight into the use of data, so the programmer has to ensure that scheduling is done efficiently. There are not many kernel interfaces available to communicate this requirement. In fact, there is only one: defining thread affinity.

Thread affinity means assigning a thread to one or more cores. The scheduler will then choose among those cores (only) when deciding where to run the thread. Even if other cores are idle they will not be considered. This might sound like a disadvantage, but it is the price one has to pay. If too many threads exclusively run on a set of cores the remaining cores might mostly be idle and there is nothing one can do except change the affinity. By default threads can run on any core.

There are a number of interfaces to query and change the affinity of a thread:

#define _GNU_SOURCE #include <sched.h> int sched_setaffinity(pid_t pid, size_t size, const cpu_set_t *cpuset); int sched_getaffinity(pid_t pid, size_t size, cpu_set_t *cpuset);

These two interfaces are meant to be used for single-threaded code. The pid argument specifies which process's affinity should be changed or determined. The caller obviously needs appropriate privileges to do this. The second and third parameter specify the bitmask for the cores. The first function requires the bitmask to be filled in so that it can set the affinity. The second fills in the bitmask with the scheduling information of the selected thread. The interfaces are declared in <sched.h>.

The cpu_set_t type is also defined in that header, along with a number of macros to manipulate and use objects of this type.

#define _GNU_SOURCE #include <sched.h> #define CPU_SETSIZE #define CPU_SET(cpu, cpusetp) #define CPU_CLR(cpu, cpusetp) #define CPU_ZERO(cpusetp) #define CPU_ISSET(cpu, cpusetp) #define CPU_COUNT(cpusetp)

CPU_SETSIZE specifies how many CPUs can be represented in the data structure. The other three macros manipulate cpu_set_t objects. To initialize an object CPU_ZERO should be used; the other two macros should be used to select or deselect individual cores. CPU_ISSET tests whether a specific processor is part of the set. CPU_COUNT returns the number of cores selected in the set. The cpu_set_t type provide a reasonable default value for the upper limit on the number of CPUs. Over time it certainly will prove too small; at that point the type will be adjusted. This means programs always have to keep the size in mind. The above convenience macros implicitly handle the size according to the definition of cpu_set_t. If more dynamic size handling is needed an extended set of macros should be used:

#define _GNU_SOURCE #include <sched.h> #define CPU_SET_S(cpu, setsize, cpusetp) #define CPU_CLR_S(cpu, setsize, cpusetp) #define CPU_ZERO_S(setsize, cpusetp) #define CPU_ISSET_S(cpu, setsize, cpusetp) #define CPU_COUNT_S(setsize, cpusetp)

These interfaces take an additional parameter with the size. To be able to allocate dynamically sized CPU sets three macros are provided:

#define _GNU_SOURCE #include <sched.h> #define CPU_ALLOC_SIZE(count) #define CPU_ALLOC(count) #define CPU_FREE(cpuset)

The CPU_ALLOC_SIZE macro returns the number of bytes which have to be allocated for a cpu_set_t structure which can handle count CPUs. To allocate such a block the CPU_ALLOC macro can be used. The memory allocated this way should be freed with CPU_FREE. The functions will likely use malloc and free behind the scenes but this does not necessarily have to remain this way.

Finally, a number of operations on CPU set objects are defined:

#define _GNU_SOURCE #include <sched.h> #define CPU_EQUAL(cpuset1, cpuset2) #define CPU_AND(destset, cpuset1, cpuset2) #define CPU_OR(destset, cpuset1, cpuset2) #define CPU_XOR(destset, cpuset1, cpuset2) #define CPU_EQUAL_S(setsize, cpuset1, cpuset2) #define CPU_AND_S(setsize, destset, cpuset1, cpuset2) #define CPU_OR_S(setsize, destset, cpuset1, cpuset2) #define CPU_XOR_S(setsize, destset, cpuset1, cpuset2)

These two sets of four macros can check two sets for equality and perform logical AND, OR, and XOR operations on sets. These operations come in handy when using some of the libNUMA functions (see Section 12).

A process can determine on which processor it is currently running using the sched_getcpu interface:

#define _GNU_SOURCE #include <sched.h> int sched_getcpu(void);

The result is the index of the CPU in the CPU set. Due to the nature of scheduling this number cannot always be 100% correct. The thread might have been moved to a different CPU between the time the result was returned and when the thread returns to userlevel. Programs always have to take this possibility of inaccuracy into account. More important is, in any case, the set of CPUs the thread is allowed to run on. This set can be retrieved using sched_getaffinity. The set is inherited by child threads and processes. Threads cannot rely on the set to be stable over the lifetime. The affinity mask can be set from the outside (see the pid parameter in the prototypes above); Linux also supports CPU hot-plugging which means CPUs can vanish from the system—and, therefore, also from the affinity CPU set.

In multi-threaded programs, the individual threads officially have no process ID as defined by POSIX and, therefore, the two functions above cannot be used. Instead <pthread.h> declares four different interfaces:

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <pthread.h>

int pthread_setaffinity_np(pthread_t th, size_t size,

const cpu_set_t *cpuset);

int pthread_getaffinity_np(pthread_t th, size_t size, cpu_set_t *cpuset);

int pthread_attr_setaffinity_np(pthread_attr_t *at,

size_t size, const cpu_set_t *cpuset);

int pthread_attr_getaffinity_np(pthread_attr_t *at, size_t size,

cpu_set_t *cpuset);

The first two interfaces are basically equivalent to the two we have already seen, except that they take a thread handle in the first parameter instead of a process ID. This allows addressing individual threads in a process. It also means that these interfaces cannot be used from another process, they are strictly for intra-process use. The third and fourth interfaces use a thread attribute. These attributes are used when creating a new thread. By setting the attribute, a thread can be scheduled from the start on a specific set of CPUs. Selecting the target processors this early—instead of after the thread already started—can be of advantage on many different levels, including (and especially) memory allocation (see NUMA in Section 6.5).

Speaking of NUMA, the affinity interfaces play a big role in NUMA programming, too. We will come back to that case shortly.

So far, we have talked about the case where the working set of two threads overlaps such that having both threads on the same core makes sense. The opposite can be true, too. If two threads work on separate data sets, having them scheduled on the same core can be a problem. Both threads fight for the same cache, thereby reducing each others effective use of the cache. Second, both data sets have to be loaded into the same cache; in effect this increases the amount of data that has to be loaded and, therefore, the available bandwidth is cut in half.

The solution in this case is to set the affinity of the threads so that they cannot be scheduled on the same core. This is the opposite from the previous situation, so it is important to understand the situation one tries to optimize before making any changes.

Optimizing for cache sharing to optimize bandwidth is in reality an aspect of NUMA programming which is covered in the next section. One only has to extend the notion of “memory” to the caches. This will become ever more important once the number of levels of cache increases. For this reason, the solution to multi-core scheduling is available in the NUMA support library. See the code samples in Section 12 for ways to determine the affinity masks without hardcoding system details or diving into the depth of the /sys filesystem.

6.5 NUMA Programming

For NUMA programming everything said so far about cache optimizations applies as well. The differences only start below that level. NUMA introduces different costs when accessing different parts of the address space. With uniform memory access we can optimize to minimize page faults (see Section 7.5) but that is about it. All pages are created equal.

NUMA changes this. Access costs can depend on the page which is accessed. Differing access costs also increase the importance of optimizing for memory page locality. NUMA is inevitable for most SMP machines since both Intel with CSI (for x86,x86-64, and IA-64) and AMD (for Opteron) use it. With an increasing number of cores per processor we are likely to see a sharp reduction of SMP systems being used (at least outside data centers and offices of people with terribly high CPU usage requirements). Most home machines will be fine with just one processor and hence no NUMA issues. But this a) does not mean programmers can ignore NUMA and b) it does not mean there are not related issues.

If one thinks about generalizations to NUMA one quickly realizes the concept extends to processor caches as well. Two threads on cores using the same cache will collaborate faster than threads on cores not sharing a cache. This is not a fabricated case:

- early dual-core processors had no L2 sharing.

- Intel's Core 2 QX 6700 and QX 6800 quad core chips, for

instance, have two separate L2 caches.

- as speculated early, with more cores on a chip and the desire to

unify caches, we will have more levels of caches.

Caches form their own hierarchy, and placement of threads on cores becomes important for sharing (or not) of caches. This is not very different from the problems NUMA is facing and, therefore, the two concepts can be unified. Even people only interested in non-SMP machines should therefore read this section.

In Section 5.3 we have seen that the Linux kernel provides a lot of information which is useful—and needed—in NUMA programming. Collecting this information is not that easy, though. The currently available NUMA library on Linux is wholly inadequate for this purpose. A much more suitable version is currently under construction by the author.

The existing NUMA library, libnuma, part of the numactl package, provides no access to system architecture information. It is only a wrapper around the available system calls together with some convenience interfaces for commonly used operations. The system calls available on Linux today are:

- mbind

- Select binding for specified memory pages to nodes.

- set_mempolicy

- Set the default memory binding policy.

- get_mempolicy

- Get the default memory binding policy.

- migrate_pages

- Migrate all pages of a process on a given set of nodes to a different set of nodes.

- move_pages

- Move selected pages to given node or request node information about pages.

These interfaces are declared in <numaif.h> which comes along with the libnuma library. Before we go into more details we have to understand the concept of memory policies.

6.5.1 Memory Policy

The idea behind defining a memory policy is to allow existing code to work reasonably well in a NUMA environment without major modifications. The policy is inherited by child processes, which makes it possible to use the numactl tool. This tool can be used to, among other things, start a program with a given policy.

The Linux kernel supports the following policies:

- MPOL_BIND

- Memory is allocated only from the given set of nodes. If this is not possible allocation fails.

- MPOL_PREFERRED

- Memory is preferably allocated from the given set of nodes. If this fails memory from other nodes is considered.

- MPOL_INTERLEAVE

- Memory is allocated equally from the specified nodes. The node is selected either by the offset in the virtual memory region for VMA-based policies, or through a free-running counter for task-based policies.

- MPOL_DEFAULT

- Choose the allocation based on the default for the region.

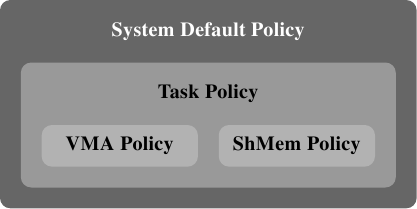

This list seems to recursively define policies. This is half true. In fact, memory policies form a hierarchy (see Figure 6.15).

Figure 6.15: Memory Policy Hierarchy

If an address is covered by a VMA policy then this policy is used. A special kind of policy is used for shared memory segments. If no policy for the specific address is present, the task's policy is used. If this is also not present the system's default policy is used.

The system default is to allocate memory local to the thread requesting the memory. No task and VMA policies are provided by default. For a process with multiple threads the local node is the “home” node, the one which first ran the process. The system calls mentioned above can be used to select different policies.

6.5.2 Specifying Policies

The set_mempolicy call can be used to set the task policy for the current thread (task in kernel-speak). Only the current thread is affected, not the entire process.

#include <numaif.h>

long set_mempolicy(int mode,

unsigned long *nodemask,

unsigned long maxnode);

The mode parameter must be one of the MPOL_* constants introduced in the previous section. The nodemask parameter specifies the memory nodes to use and maxnode is the number of nodes (i.e., bits) in nodemask. If MPOL_DEFAULT is used the nodemask parameter is ignored. If a null pointer is passed as nodemask for MPOL_PREFERRED the local node is selected. Otherwise MPOL_PREFERRED uses the lowest node number with the corresponding bit set in nodemask.

Setting a policy does not have any effect on already-allocated memory. Pages are not automatically migrated; only future allocations are affected. Note the difference between memory allocation and address space reservation: an address space region established using mmap is usually not automatically allocated. The first read or write operation on the memory region will allocate the appropriate page. If the policy changes between accesses to different pages of the same address space region, or if the policy allows allocation of memory from different nodes, a seemingly uniform address space region might be scattered across many memory nodes.

6.5.3 Swapping and Policies

If physical memory runs out, the system has to drop clean pages and save dirty pages to swap. The Linux swap implementation discards node information when it writes pages to swap. That means when the page is reused and paged in the node which is used will be chosen from scratch. The policies for the thread will likely cause a node which is close to the executing processors to be chosen, but the node might be different from the one used before.

This changing association means that the node association cannot be stored by a program as a property of the page. The association can change over time. For pages which are shared with other processes this can also happen because a process asks for it (see the discussion of mbind below). The kernel by itself can migrate pages if one node runs out of space while other nodes still have free space.

Any node association the user-level code learns about can therefore be true for only a short time. It is more of a hint than absolute information. Whenever accurate knowledge is required the get_mempolicy interface should be used (see Section 6.5.5).

6.5.4 VMA Policy

To set the VMA policy for an address range a different interface has to be used:

#include <numaif.h>

long mbind(void *start, unsigned long len,

int mode,

unsigned long *nodemask,

unsigned long maxnode,

unsigned flags);

This interface registers a new VMA policy for the address range [start, start + len). Since memory handling operates on pages the start address must be page-aligned. The len value is rounded up to the next page size.

The mode parameter specifies, again, the policy; the values must be chosen from the list in Section 6.5.1. As with set_mempolicy, the nodemask parameter is only used for some policies. Its handling is identical.

The semantics of the mbind interface depends on the value of the flags parameter. By default, if flags is zero, the system call sets the VMA policy for the address range. Existing mappings are not affected. If this is not sufficient there are currently three flags to modify this behavior; they can be selected individually or together:

- MPOL_MF_STRICT

- The call to mbind will fail if not all pages are on the nodes specified by nodemask. In case this flag is used together with MPOL_MF_MOVE and/or MPOL_MF_MOVEALL the call will fail if any page cannot be moved.

- MPOL_MF_MOVE

- The kernel will try to move any page in the address range allocated on a node not in the set specified by nodemask. By default, only pages used exclusively by the current process's page tables are moved.

- MPOL_MF_MOVEALL

- Like MPOL_MF_MOVE but the kernel will try to move all pages, not just those used by the current process's page tables alone. This has system-wide implications since it influences the memory access of other processes—which are possibly not owned by the same user—as well. Therefore MPOL_MF_MOVEALL is a privileged operation (CAP_NICE capability is needed).

Note that support for MPOL_MF_MOVE and MPOL_MF_MOVEALL was added only in the 2.6.16 Linux kernel.

Calling mbind without any flags is most useful when the policy for a newly reserved address range has to be specified before any pages are actually allocated.

void *p = mmap(NULL, len, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_ANON, -1, 0); if (p != MAP_FAILED) mbind(p, len, mode, nodemask, maxnode, 0);

This code sequence reserve an address space range of len bytes and specifies that the policy mode referencing the memory nodes in nodemask should be used. Unless the MAP_POPULATE flag is used with mmap, no memory will have been allocated by the time of the mbind call and, therefore, the new policy applies to all pages in that address space region.

The MPOL_MF_STRICT flag alone can be used to determine whether any page in the address range described by the start and len parameters to mbind is allocated on nodes other than those specified by nodemask. No allocated pages are changed. If all pages are allocated on the specified nodes, the VMA policy for the address space region will be changed according to mode.

Sometimes the rebalancing of memory is needed, in which case it might be necessary to move pages allocated on one node to another node. Calling mbind with MPOL_MF_MOVE set makes a best effort to achieve that. Only pages which are solely referenced by the process's page table tree are considered for moving. There can be multiple users in the form of threads or other processes which share that part of the page table tree. It is not possible to affect other processes which happen to map the same data. These pages do not share the page table entries.

If both MPOL_MF_STRICT and MPOL_MF_MOVE are passed to mbind the kernel will try to move all pages which are not allocated on the specified nodes. If this is not possible the call will fail. Such a call might be useful to determine whether there is a node (or set of nodes) which can house all the pages. Several combinations can be tried in succession until a suitable node is found.

The use of MPOL_MF_MOVEALL is harder to justify unless running the current process is the main purpose of the computer. The reason is that even pages that appear in multiple page tables are moved. That can easily affect other processes in a negative way. This operation should thus be used with caution.

6.5.5 Querying Node Information

The get_mempolicy interface can be used to query a variety of facts about the state of NUMA for a given address.

#include <numaif.h>

long get_mempolicy(int *policy,

const unsigned long *nmask,

unsigned long maxnode,

void *addr, int flags);

When get_mempolicy is called without a flag set in flags, the information about the policy for address addr is stored in the word pointed to by policy and in the bitmask for the nodes pointed to by nmask. If addr falls into an address space region for which a VMA policy has been specified, information about that policy is returned. Otherwise information about the task policy or, if necessary, system default policy will be returned.

If the MPOL_F_NODE flag is set in flags, and the policy governing addr is MPOL_INTERLEAVE, the value stored in the word pointed to by policy is the index of the node on which the next allocation is going to happen. This information can potentially be used to set the affinity of a thread which is going to work on the newly-allocated memory. This might be a less costly way to achieve proximity, especially if the thread has yet to be created.

The MPOL_F_ADDR flag can be used to retrieve yet another completely different data item. If this flag is used, the value stored in the word pointed to by policy is the index of the memory node on which the memory for the page containing addr has been allocated. This information can be used to make decisions about possible page migration, to decide which thread could work on the memory location most efficiently, and many more things.

The CPU—and therefore memory node—a thread is using is much more volatile than its memory allocations. Memory pages are, without explicit requests, only moved in extreme circumstances. A thread can be assigned to another CPU as the result of rebalancing the CPU loads. Information about the current CPU and node might therefore be short-lived. The scheduler will try to keep the thread on the same CPU, and possibly even on the same core, to minimize performance losses due to cold caches. This means it is useful to look at the current CPU and node information; one only must avoid assuming the association will not change.

libNUMA provides two interfaces to query the node information for a given virtual address space range:

#include <libNUMA.h>

int NUMA_mem_get_node_idx(void *addr);

int NUMA_mem_get_node_mask(void *addr,

size_t size,

size_t __destsize,

memnode_set_t *dest);

NUMA_mem_get_node_mask sets in dest the bits for all memory nodes on which the pages in the range [addr, addr+size) are (or would be) allocated, according to the governing policy. NUMA_mem_get_node only looks at the address addr and returns the index of the memory node on which this address is (or would be) allocated. These interfaces are simpler to use than get_mempolicy and probably should be preferred.

The CPU currently used by a thread can be queried using sched_getcpu (see Section 6.4.3). Using this information, a program can determine the memory node(s) which are local to the CPU using the NUMA_cpu_to_memnode interface from libNUMA:

#include <libNUMA.h>

int NUMA_cpu_to_memnode(size_t cpusetsize,

const cpu_set_t *cpuset,

size_t memnodesize,

memnode_set_t *

memnodeset);

A call to this function will set (in the memory node set pointed to by the fourth parameter) all the bits corresponding to memory nodes which are local to any of the CPUs in the set pointed to by the second parameter. Just like CPU information itself, this information is only correct until the configuration of the machine changes (for instance, CPUs get removed and added).

The bits in the memnode_set_t objects can be used in calls to the low-level functions like get_mempolicy. It is more convenient to use the other functions in libNUMA. The reverse mapping is available through:

#include <libNUMA.h>

int NUMA_memnode_to_cpu(size_t memnodesize,

const memnode_set_t *

memnodeset,

size_t cpusetsize,

cpu_set_t *cpuset);

The bits set in the resulting cpuset are those of the CPUs local to any of the memory nodes with corresponding bits set in memnodeset. For both interfaces, the programmer has to be aware that the information can change over time (especially with CPU hot-plugging). In many situations, a single bit is set in the input bit set, but it is also meaningful, for instance, to pass the entire set of CPUs retrieved by a call to sched_getaffinity to NUMA_cpu_to_memnode to determine which are the memory nodes the thread ever can have direct access to.

6.5.6 CPU and Node Sets

Adjusting code for SMP and NUMA environments by changing the code to use the interfaces described so far might be prohibitively expensive (or impossible) if the sources are not available. Additionally, the system administrator might want to impose restrictions on the resources a user and/or process can use. For these situations the Linux kernel supports so-called CPU sets. The name is a bit misleading since memory nodes are also covered. They also have nothing to do with the cpu_set_t data type.

The interface to CPU sets is, at the moment, a special filesystem. It is usually not mounted (so far at least). This can be changed with

mount -t cpuset none /dev/cpuset

Of course the mount point /dev/cpuset must exist. The content of this directory is a description of the default (root) CPU set. It comprises initially all CPUs and all memory nodes. The cpus file in that directory shows the CPUs in the CPU set, the mems file the memory nodes, the tasks file the processes.

To create a new CPU set one simply creates a new directory somewhere in the hierarchy. The new CPU set will inherit all settings from the parent. Then the CPUs and memory nodes for new CPU set can be changed by writing the new values into the cpus and mems pseudo files in the new directory.

If a process belongs to a CPU set, the settings for the CPUs and memory nodes are used as masks for the affinity and memory policy bitmasks. That means the program cannot select any CPU in the affinity mask which is not in the cpus file for the CPU set the process is using (i.e., where it is listed in the tasks file). Similarly for the node masks for the memory policy and the mems file.

The program will not experience any errors unless the bitmasks are empty after the masking, so CPU sets are an almost-invisible means to control program execution. This method is especially efficient on large machines with lots of CPUs and/or memory nodes. Moving a process into a new CPU set is as simple as writing the process ID into the tasks file of the appropriate CPU set.

The directories for the CPU sets contain a number of other files which can be used to specify details like behavior under memory pressure and exclusive access to CPUs and memory nodes. The interested reader is referred to the file Documentation/cpusets.txt in the kernel source tree.

6.5.7 Explicit NUMA Optimizations

All the local memory and affinity rules cannot help out if all threads on all the nodes need access to the same memory regions. It is, of course, possible to simply restrict the number of threads to a number supportable by the processors which are directly connected to the memory node. This does not take advantage of SMP NUMA machines, though, and is therefore not a real option.

If the data in question is read-only there is a simple solution: replication. Each node can get its own copy of the data so that no inter-node accesses are necessary. Code to do this can look like this:

void *local_data(void) {

static void *data[NNODES];

int node =

NUMA_memnode_self_current_idx();

if (node == -1)

/* Cannot get node, pick one. */

node = 0;

if (data[node] == NULL)

data[node] = allocate_data();

return data[node];

}

void worker(void) {

void *data = local_data();

for (...)

compute using data

}

In this code the function worker prepares by getting a pointer to the local copy of the data by a call to local_data. Then it proceeds with the loop, which uses this pointer. The local_data function keeps a list of the already allocated copies of the data around. Each system has a limited number of memory nodes, so the size of the array with the pointers to the per-node memory copies is limited in size. The NUMA_memnode_system_count function from libNUMA returns this number. If the pointer for the current node, as determined by the NUMA_memnode_self_current_idx call, is not yet known a new copy is allocated.

It is important to realize that nothing terrible happens if the threads get scheduled onto another CPU connected to a different memory node after the sched_getcpu system call. It just means that the accesses using the data variable in worker access memory on another memory node. This slows the program down until data is computed anew, but that is all. The kernel will always avoid gratuitous rebalancing of the per-CPU run queues. If such a transfer happens it is usually for a good reason and will not happen again for the near future.

Things are more complicated when the memory area in question is writable. Simple duplication will not work in this case. Depending on the exact situation there might a number of possible solutions.

For instance, if the writable memory region is used to accumulate results, it might be possible to first create a separate region for each memory node in which the results are accumulated. Then, when this work is done, all the per-node memory regions are combined to get the total result. This technique can work even if the work never really stops, but intermediate results are needed. The requirement for this approach is that the accumulation of a result is stateless, i.e., it does not depend on the previously collected results.

It will always be better, though, to have direct access to the writable memory region. If the number of accesses to the memory region is substantial, it might be a good idea to force the kernel to migrate the memory pages in question to the local node. If the number of accesses is really high, and the writes on different nodes do not happen concurrently, this could help. But be aware that the kernel cannot perform miracles: the page migration is a copy operation and as such it is not cheap. This cost has to be amortized.

6.5.8 Utilizing All Bandwidth

The numbers in Figure 5.4 show that access to remote memory when the caches are ineffective is not measurably slower than access to local memory. This means a program could possibly save bandwidth to the local memory by writing data it does not have to read again into memory attached to another processor. The bandwidth of the connection to the DRAM modules and the bandwidth of the interconnects are mostly independent, so parallel use could improve overall performance.

Whether this is really possible depends on many factors. One really

has to be sure that caches are ineffective since otherwise the

slowdown related to remote accesses is measurable. Another big

problem is whether the remote node has any needs for its own memory

bandwidth. This possibility must be examined in detail before the

approach is taken. In theory, using all the bandwidth available to a

processor can have positive effects. A family 10h Opteron processor

can be directly connected to up to four other processors. Utilizing

all that additional bandwidth, perhaps coupled with appropriate

prefetches (especially prefetchw) could lead to improvements if

the rest of the system plays along.

| Index entries for this article | |

|---|---|

| GuestArticles | Drepper, Ulrich |

(Log in to post comments)

Memory part 6: More things programmers can do

Posted Oct 31, 2007 19:11 UTC (Wed) by phip (guest, #1715) [Link]

Figure 6.11 shows the equivalent measurements when running the code on a single processor, quad core machine (Intel Core 2 QX 6700). Even with this processor's two separate L2s the test case does not show any scalability issues. There is a slight overhead when using the same cache line more than once but it does not increase with the number of cores. {I cannot explain the lower number when all four cores are used but it is reproducible.}Intel's Core 2 QX 6700 and QX 6800 quad core chips, for instance, have two separate L2 caches.

If I understand correctly, cores 0 and 1 share an L2, and cores 2 and 3 share a second L2.

With 4 cores, core 2 and core 3 will effectively prefetch lines into the shared L2 for each other. With only 3 cores, core 2 has to pay the full penalty for all its L2 cache misses.

Memory part 6: More things programmers can do

Posted Nov 1, 2007 17:22 UTC (Thu) by ajross (guest, #4563) [Link]

Yes. The quad core chips are basically two dual core CPUs with some SMP glue logic and a unified memory controller.

Intel Quad-core implementation

Posted Nov 9, 2007 11:00 UTC (Fri) by anton (subscriber, #25547) [Link]

The current Intel quad core packages are two dual-core chips in a multi-chip module (MCM), connected to a common bus. There is no glue logic (SMP logic is on each of the chips), and the memory controller is in a different package (the MCH).

Versions?

Posted Oct 31, 2007 20:38 UTC (Wed) by ncm (guest, #165) [Link]

It would help a great deal, for portability and deployment, if we knew which are the earliest versions of Linux kernel and Glibc that support each of the facilities described.

Missing closing tag

Posted Oct 31, 2007 23:41 UTC (Wed) by ohcamacj (guest, #45012) [Link]

The malformed closing </b> tag on Load Lock/Store Conditional (LL/SC)</b</dt> makes half the page be in bold text. (In Opera and IE; Mozilla* treats it as a closing tag.)

LWN: Front Page

Posted Nov 1, 2007 12:47 UTC (Thu) by dfarning (guest, #24102) [Link]

I just wanted to let the editors know that this was one of your best front pages. A State of... article, a level headed analysis of a current event, and a great technical article! Outstanding David

Memory part 6: More things programmers can do

Posted Nov 1, 2007 14:06 UTC (Thu) by cruff (subscriber, #7201) [Link]

Err, what's wrong with using the standard compliant

const int bar = 2

instead of attributes?

Memory part 6: More things programmers can do

Posted Nov 1, 2007 15:42 UTC (Thu) by madscientist (subscriber, #16861) [Link]

Not sure exactly which part of the article you're talking about, but Ulrich does say: > If the programmer marks the variables correctly with const, the tool chain > will move the variables away from the normal variables into the .rodata > (read-only data) or .data.rel.ro (read-only after relocation) section [...] > No other special action is required. If, for some reason, variables cannot > be marked correctly with const, the programmer can influence their > placement by assigning them to a special section.

Memory part 6: More things programmers can do

Posted Nov 4, 2007 20:19 UTC (Sun) by jengelh (subscriber, #33263) [Link]

>6.4.2 Atomicity Optimizations > >Adding a relatively expensive operation like a conditional jump (expensive in case the branch prediction fails) seems to be counter productive. The Linux kernel uses a smarter strategy, where it patches away the 'lock' insn by modifying its own code and replace it with NOPs, making it run through neither a jump nor an unconditional 'lock'. ( http://lwn.net/Articles/164121/ ) It does not work reliably for userspace due to W^X and such, oh well, but at least it does for the kernel.

Memory part 6: More things programmers can do

Posted Nov 6, 2007 15:50 UTC (Tue) by balbir_singh (subscriber, #34142) [Link]

I would really like to get a .pdf or a good printable document of all articles in this series combined, once the series is complete. You could make the pdf subscriber only, if required. Balbir

Document in PDF form

Posted Nov 6, 2007 15:55 UTC (Tue) by corbet (editor, #1) [Link]

Ulrich plans to release a full PDF of the document once the whole thing has been serialized here (which is close - only two segments to go).

Memory part 6: More things programmers can do

Posted Nov 9, 2007 16:50 UTC (Fri) by afachat (guest, #48961) [Link]

I think there is an inherent semantical difference between LL/SC and CAS. In the first case the store fails when another CPU has written to the memory location, no matter what the value is. Even if the other CPU writes the exactly same value that was there before, SC will fail. Not so with CAS, that fails only if the other CPU has written a different value. From a CPU designer point of view those are really different operations: LL/SC needs to remember the address loaded with LL, and set a flag once another CPU requests ownership of that address (to write), so that SC can fail. CAS needs to actually lock the memory location for the duration of the read-compare-store. As it's atomic, I assume that on start of the opcode the CPU requests ownership for the variable's address, then reads the value to compare it. What happens if during this time interval another CPU requests ownership of that address? The opcode is atomic, so the other CPU must wait as long as the compare and store operation is going on? I.e. the bus operation is stalled for that amount of time, reducing memory bandwidth? Or how does it work? For that reason I have always thought that LL/SC was the more efficient algorithm, as it does not lock the bus, thus not forcing other CPUs to wait. It probably depends on the amount of collisions (two CPUs competing for the same variable at the same time) one expects. Low collision numbers allow for LL/SC to have a low number of loops due to failing SCs, while high collisions would lead to an increasing number of loops in LL/SC so that CAS would be more efficient.

SC(var, newval)) missing the address parameter

Posted Nov 13, 2007 13:20 UTC (Tue) by tyhik (guest, #14747) [Link]

"Here we have to use a special load instruction (LL) and we do not have to pass the current value of the memory location to SC since the processor knows if the memory location has been modified in the meantime." How precisely the CPU knows the location, depends on arch. According to "MIPS Architecture for Programmers", MIPS cpu-s remember the block of memory previously accessed with LL; depending on CPU, the block may be from word size to page size. The sc instruction on MIPS has the address parameter. Therefore, in general, the "SC(var, newval)" should have the address parameter too.